What could be cooler than accidentally running across one of my favorite “John Cheever”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cheever stories, “Some People, Places, and Things That Will Not Appear In My Novel”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/11/12/1960_11_12_054_TNY_CARDS_000265256, in the The Complete New Yorker?

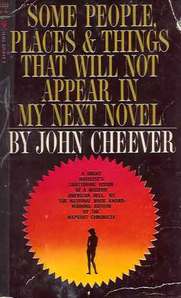

Way cooler: realizing that this story, from the November 12, 1960, issue, is longer and more revealing than the cut-down version that appeared in Cheever’s 1961 collection Some People, Places & Things That will Not Appear in My Next Novel (note that added “next”), with a new title: “A Miscellany of Characters That Will Not Appear.” (The latter version is also in his famous collection The Stories of John Cheever.)

Yup, that’s right: he hacked it before anthologizing it.

Both versions are exactly what the title promises: a list of things Cheever (or his narrator) finds irritating, despicable, or disappointing in contemporary fiction. The revised version is seven items long; the original runs to 11, plus a coda. More of an essay than a story, its spleen still startles, even after nearly 50 years.

When he revised it, Cheever cut item 5, one of several cheap shots in the original. It reads, in its entirety, “The dumb blonde, because she’s no dumber than you, whoever you are.” He was right to think better of it (though I confess I like the audacity of its pointed finger), as well as item 7, his swipe at “J. D. Salinger”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._D._Salinger, whose success he envied:

Almost all autobiographical characters who describe themselves as being under the age of reason, coherence, and consent; i.e., I mean I’m this crazy, shook-up, sexy kid of thirteen with these phony parents, I mean my parents are so phony it makes me puke to think about them and that’s why I live in Mexico to keep away from these phony parents.

But I was sorry to see several other items go, short fictional sketches that displayed all of Cheever’s compassion and flair for the nomenclature of despair and regret. Item 4, for example, where he describes the jaundiced host of a suburban cocktail party, now keenly aware of his mortality:

He knew that time passed over the apple, over the rose, that time passed even over the old football in the coat closet, but he was astonished to find that time had passed over him. Why hadn’t someone told him? What had become of that form that used to cause so much consternation at the edge of the swimming pool?

It’s funny to think of this ordinary man musing on his own death with such graceful phrases, but it’s part of Cheever’s magic that he invests his characters so generously. Of the drunk advertising man in item 10, Cheever writes,

Here we see, as on a sandy point we see the working of two tides, how the powers of his exaltation and his misery, his lusts, and his aspirations have stamped a wilderness of wrinkles onto the dark and pouchy skin. He may have tired his eyes looking at Vega through a telescope or reading Keats by a dim light, but his gaze seems hangdog and impure.

Vega? Keats? Not a chance. For Cheever’s characters, though, these are real possibilities. Death and failure may never be far from their minds, but he is quick to grant them depth and protect them from judgment.

For example, when Charlie Pilstrom in item 6 converses with his neighbors while waiting on a train platform, he makes sure they all know how demanding his job is. Then the express train arrives, blows open his briefcase, and reveals his lies—he has no work to go to. In steps the narrator:

His unimportance, his idleness, his loneliness, and his unemployment are all exposed, but the scene is invalid because of its maliciousness, and because couldn’t most of us be equally exposed by a gust of wind, a lost button, or some other blackmailing turn of events? It’s too damned small.

Aside from Salinger, whose work exactly is Cheever irritated by? I’m not sure. I’m insufficiently steeped in mid-century American literature to be able to identify all of his targets. But the “pretty girl at the Princeton-Dartmouth Rugby game” (item 1) is actually a type I’m only familiar with from Cheever himself, and “lushes” (item 10), homosexuality (item 11), and fear of failure (items 2, 6, and 10) are all things that obsessed Cheever himself, as we know from his fiction, letters, and journals. It’s impossible to read “Some People,” in fact, without suspecting that the pathetic fallacy may not in this case be a fallacy:

And while we are about it, out go all those homosexuals who have taken such a dominating position in recent fiction. Isn’t it time that we embraced the indiscretion and inconstancy of the flesh and moved on?

Surely, that’s Cheever himself, wishing desperately not to have to hide? He’s frustrated, yes, with contemporary fiction and its flaws, but I think he must also have been frustrated with what he took to be the shortcomings of his own work.

Just look at item 2, which does not appear in the revised version (though it might have reappeared in his next novel). It gives us the story’s manifesto:

Fiction is art, and art is the triumph over chaos (no less), and we can accomplish this only by the most vigilant exercise of choice, but in a world that changes more swiftly than we can perceive there is always the danger that our powers of selection will be mistaken and that the vision we serve will come to nothing. We admire decency and we despise death, but even the mountains seem to move in the space of a night and perhaps the exhibitionist at the corner of Chestnut and Elm Streets is more significant than the lovely woman with a bar of sunlight in her hair, putting a fresh piece of cuttlefish into the nightingale’s cage. Our bearings are rudimentary, but surely sentimentality and picturesqueness have no place in our scheme, so we will throw out, for example, that old crone who, in the autumn dusk, roasts and sells chestnuts on the steps of the Ponte Sant’Angelo on the east bank of the Tiber.

Old crones, chestnuts, and autumn dusk—what phrases could be more typical of Cheever? Whatever the case, the story is a thorny little piece of metafiction, and I can only imagine what TNY readers of 1960 thought of it, when placed beside the more conventional work of “Mary Lavin”:http://emdashes.com/2008/07/mary-lavin-catch-the-wave.php, “John Updike”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/06/18/1960_06_18_039_TNY_CARDS_000260464, “V.S. Pritchett”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/07/16/1960_07_16_030_TNY_CARDS_000262147, and “Ruth Prawer Jhabvala”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/04/30/1960_04_30_040_TNY_CARDS_000263503. So spare some pity for the poor TNY intern who had to write the “story’s summary”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/11/12/1960_11_12_054_TNY_CARDS_000265256

for the magazine’s index:

Writer does not intend to write about drunks in his novel. He does a brief description of part of the story of a drunk, who is an advertising man, who loses his job.