_Pollux writes_:

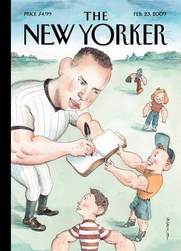

“I know I can make a difference on this issue,” baseball player Alex Rodriguez, called A-Rod by some (and A-Fraud by others), has “recently remarked”:http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/18/sports/baseball/18yankees.html in regards to educating the young on the dangers of steroid use. Blitt’s February 23, 2009 _New Yorker_ cover depicts just exactly what difference Rodriguez will make on today’s youth: bigger biceps.

Blitt’s cartoon takes place in an idyllic, as-American-as-apple-pie parkland: Rodriguez blithely and humbly signs young Timmy’s autograph book as other local kids enthusiastically gather around their hero. Rodriguez’s arms are as large as coiled pythons, and the children have imitated their hero by hopping themselves up on illegal ‘roids.

In response to Blitt’s now infamous Obama cover, the cartoonist “has stated”:http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2008/07/13/barry-blitt-addresses-his_n_112432.html that “it seemed to me that depicting the concept would show it as the fear-mongering ridiculousness that it is.” Fair enough, but Blitt’s new cover, which he calls “Off Base,” strikes an ambivalent note. As with the Obama cover, Blitt once again produces an ambiguous message. Is Blitt capturing and satirizing fears regarding Rodriguez’s promise to educate kids on the dangers of steroids? Or is he attacking Rodriguez directly? Blitt’s watercolors and linework haven’t created the monster that the cover itself suggests that Rodriguez may be, but rather a sympathetic, benevolent figure. The drawing inhabits the soft towns of Norman Rockwell rather than the ruthless landscapes of Hogarth and Daumier. Blitt, although immensely talented as an artist, wants it both ways again: he wants to represent fear-mongering ridiculousness without agreeing with this fear-mongering ridiculousness himself.

But that really isn’t possible, and this iffiness has produced a less than successful cover. Whether you care about baseball or not, A-Rod’s cheating and perjury make him a less than attractive figure in an American landscape that already seems to be ravaged more than usual by cheats and liars, from the corked bats and Primobolan in the world of athletics to the corked hedge funds of Madoffian financing, from Bush’s yellowcake uranium claims to Blagojevich’s sleazy influence peddling and pay-to-play schemes. It isn’t the time for fuzzy and hesitant artistic attacks or for pulling punches. Blitt once again has created a cover whose actual target is unclear. Is Rodriguez the actual target of the attack or is the target actually our fears that somehow Rodriguez will push Decadurabolin and Sustanon on unsuspecting children?

Blitt has swung and missed.

Emdashes

Modern times between the lines