Emdashes—Modern Times Between the Lines

The Basics:

About Emdashes | Email us

Ask the Librarians

Best of Emdashes: Hit Parade

A Web Comic: The Wavy Rule

Features & Columns:

Headline Shooter

On the Spot

Looked Into

Sempé Fi: Cover Art

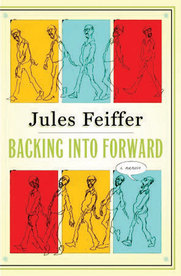

(Review) Back to Back: Jules Feiffer's Backing Into Forward

Filed under: Looked Into Tagged: Alan Dunn, books, cartoons, Charles Addams, comics, Frank Modell, George Price, Gluyas Williams, Helen Hokinson, Jules Feiffer, memoirs, Peter Arno, Pollux, reviews, Sam Cobean, Whitney Darrow, Will Eisner

Pollux writes:

On a recent trip to New York, I was accompanied by Jules Feiffer’s autobiography, Backing Into Forward (published by Nan A. Talese). Between snatches of fitful, airborne sleep and occasional glances at a muted version of Hachiko: A Dog’s Story, Feiffer’s book served as a great and inspiring companion.

Backing Into Forward can be read non-linearly. Feiffer’s book reads less like a traditional autobiography than a collection of self-contained, stand-alone essays. Like Feiffer’s comic strips for The Village Voice, each piece throws light on a particular anxiety, time period, or person. Backing Into Forward has chapters named, for example, “The Jewish Mother Joke,” “Hackwork,” “Mimi,” “Lucking Into the Zeitgeist,” and “Process.”

The chapter named “Process,” for example, consists of a single page. Feiffer describes his process for arriving—or not arriving—at a completed comic strip. “I’d be humming along nicely—and then I’d arrive at what should have been the last panel without a thought in my head. I didn’t know how to end the thing. So I’d stash the idea in a drawer and forget it. A year or ten or twenty-five went by and, searching for something else, I’d come across the unfinished idea. Thirty seconds later the ending would announce itself. I’d draw it and send it in. Twenty-five years in the making: a comic strip.”

Feiffer skips backward and forward into time as he writes about his childhood in the Bronx, his journey to the West Coast and back again as a hitchhiker, his time in the army, his mother, his rise to fame, and his entry into the world of comics via work as Will Eisner’s gopher and subsequent ghost writer. As he tells it, Feiffer was a wimpy kid who found refuge in the world of comics. As a young man, he was tongue-tied and awkward around women. Feiffer is funny and honest about what fame did to his relations with women: now they had to nervously come up with an opening line if they wanted to talk to him.

The same distinctive voice that reverberates through Sick Sick Sick and Feiffer is here: Feiffer is both acerbic and candid about his childhood, talent, family, doubts and frustrations (both sexual and creative), and fears (most of all, his fears). But it is an autobiography about hope and determination as well: nothing, not even a Korean War-era draft, an overbearing mother, or heartbreak- could stop Feiffer’s goal of becoming a comics artist.

Feiffer’s work appeared often in The New Yorker, but, interestingly, he writes that it was the dream of newspaper work that propelled him towards his goal. “Although I had been an admirer of The New Yorker since childhood, the magazine had never played a part in how I worked or thought about work… [A]s much as I loved the work of Peter Arno, Charles Addams, Whitney Darrow, George Price, Helen Hokinson, Gluyas Williams, Alan Dunn, Sam Cobean, Frank Modell, and other New Yorker regulars, I could not imagine myself appearing in their magazine.”

It is his candor that made his comics, plays, children’s stories, and screenplays unique and mordant examinations of American Anxiety from the Vietnam era to our present decade. Feiffer is still relevant. His Obama! Ourbama! print captures the optimism that took hold of many of us at the beginnings of 2009, sizeable shreds and shards of which still remain.

Backing Into Forward includes many illustrations and photographs, and it ends with three pages of drawings in a chapter called “Last Panels.” Feiffer, in tux and top hat, ends with a Sick Sick Sick-style farewell: “Now the great thing about being a cartoonist…is that you can draw yourself as anyone you like….So excuse me…As I finish my dance.”