A column in which Jon Michaud and Erin Overbey, The New Yorker’s head librarians, answer your questions about the magazine’s past and present. E-mail your own questions for Jon and Erin; the column has now moved to The New Yorker‘s Back Issues blog. Illustration for Emdashes by Lara Tomlin; other images are courtesy of The New Yorker.

Q. When did Robert Day start drawing for The New Yorker? For how long? How many drawings were published, and do you have a favorite?

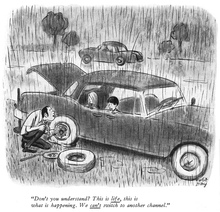

Erin writes: Robert Day, a longtime cartoonist and cover artist at the magazine, began contributing to The New Yorker in September of 1931. Prior to joining the magazine, Day had been a freelance cartoonist at the New York Herald Tribune. In a career at the magazine that spanned forty-five years, from 1931 to 1976, he published nearly eighteen hundred cartoons and eight covers. Many times, the prolific cartoonist had more than one cartoon in an issue. One of my favorite Day cartoons ran in the July 25, 1970, issue. In it, a father fixes a flat tire along a busy highway and says to his two young children, “Don’t you understand? This is life, this is what is happening. We can’t switch to another channel.” Day died in 1985, at the age of eighty-four. In the obituary The New Yorker ran after his death, former art editor Lee Lorenz wrote of Day: “His unadorned brush drawings, with their juicy, effortlessly flowing line, were as elegant as anything we have ever published.”

Q. What is the breakdown of The New Yorker‘s readership between New York and the rest of the world?

Jon writes: According to 2005 data from the Audit Bureau of Circulation, The New Yorker has 183,732 subscribers in the New York metropolitan area, representing 19 percent of its total circulation of 1,051,919. (Circulation includes both paid subscriptions and newsstand sales.) The New Yorker has 965,341 subscribers in the United States, 14,044 subscribers in Canada, and 20,453 subscribers in the rest of the world. The state with the most subscribers is California, with 177,814; the state with the fewest is South Dakota, with 723. The smallest market for The New Yorker in North America is the Yukon Territory, with seven subscribers. There are several countries–including Malawi, Brunei, the Dominican Republic, and Albania–with only one subscriber to the magazine. The current subscription rate is $52 domestic, $90 for Canada, and $112 for other countries.

In its early years, the magazine was not above poking fun at its own international subscription rates. A spoof in the October 2, 1926, issue took the form of a letter from a reader in Vevey, Switzerland, complaining about the cost of subscribing to The New Yorker ($7): “Do you know what I could get with seven whole American dollars over here? Merely (choice) six bottles of real Gordon gin…two pairs of natty sport shoes…two pairs of white flannel trousers, a return ticket to Paris…or the services of a gifted Swiss cook-waitress-chambermaid for almost one month.”

We don’t know what the going rate for domestic help in Switzerland is these days, but the price of an international subscription to The New Yorker will still buy six bottles of Gordon’s gin from a Manhattan liquor store ($18.99 per 1.75 liter bottle), a pair of Zoom LeBron IIIs from Nike ($110), one new pair of flannel pants from the Orvis catalog ($98), or a one-way second-class ticket on the TGV between Geneva and Paris (70 Euros or about $90, if purchased a month in advance).

Q. What are some departments that no longer exist? Did the magazine ever have regular, say, tennis or vaudeville reviews?

Erin writes: While certain departments–such as A Reporter at Large and The Current Cinema–have existed since the start of the magazine, many others have fallen out of fashion. In some cases, department titles have simply evolved over time. A few of my personal favorites of these extinct departments include That Was New York (1928-81), Of All Things (1925-51), and H. L. Mencken’s Days of Innocence (1941-43).

Other extinct departments are equally varied. Broadway Rackets (1927), a column by Jack Wynn, concerned mob rackets and scams operating in midtown Manhattan at the time. Speakeasy Nights (1927-29), by Niven Busch, Jr., reviewed Manhattan speakeasies during the Prohibition era. Ring Lardner’s Over the Waves (1932-33) discussed popular radio programs of the day. The Army Life (1941-44), by E. J. Kahn, was a chronicle of soldiers’ activities around the globe during the Second World War. And Notes for a Gazetteer (1959-66), written by Philip Hamburger, explored the cultures of various cities across the nation and was a sort of precursor to Calvin Trillin’s U.S. Journal.

The magazine also ran a regular Football column from 1926 to 1980 (written primarily by R. E. M. Whitaker), a Tennis Courts (or On the Courts) column from 1926 to 1947, and a Yachts and Yachtsmen column from 1927 to 1941. Other sports the magazine used to cover on a regular basis include boxing, horse racing, golf, rowing, polo, and hockey. About the House (1926-74), an interior-decorating column, and Lois Long’s Feminine Fashions (1926-82) round out an eclectic assortment of extinct departments.

Some departments that stop running in the magazine later reappear in a slightly different version: the Tables for Two restaurant column ran as a stand-alone column from 1926 to 1962, and then later re-emerged in the Goings On About Town section in 1995. Similarly, The Wayward Press (written primarily by A. J. Liebling) ran from 1927 to 1963, and was re-introduced in 1999 by Hendrik Hertzberg; and the Shouts & Murmurs “casual” (1929-34), which was originally written by Alexander Woollcott, reappeared in 1992.

Many of these extinct departments reflect a playful sensibility. What are we to make of department names like the Department of Correction, Amplification & Abuse, or the Department of Misquotation, Correction & Inter-Urban Relations? Equally droll are When New York Was Really Wicked (1927-28), Our Windswept Correspondents (1954), and A Reporter in Bed (1942-50). As I pored over the vast archive of departments, I wondered if any headings could have been left unaddressed. Apparently, there is at least one. According to The Years with Ross (1957), by James Thurber, Harold Ross once told Thurber that he’d “never run a department about dogs.”

Q. Are there plans to update The Complete New Yorker?

Jon writes: Yes. An update is just about to be released. It includes issues from February 2005 through the end of April 2006. The update, which comes in the form of a new disk 1 for the DVD set, costs $19.99 and is available from The New Yorker Store at www.newyorkerstore.com.

The update has been designed to integrate seamlessly with the first eighty years, and the user’s reading lists and notes will be preserved. In addition to providing fourteen months of additional issues, it features modifications and improvements to the archive’s search engine. The update will also be included on the portable hard drive version of The Complete New Yorker, which is being released on September 18.

Q. Why did it take so long for The New Yorker to get a table of contents?

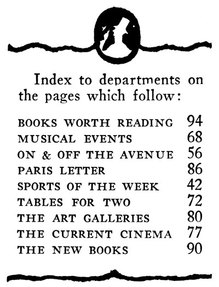

Erin writes: The New Yorker famously did not have a conventional table of contents until 1969. But the magazine actually started running a small index of articles or departments with the March 5, 1927, issue; it was originally located in the middle of each issue and later moved to the first page of the Goings On About Town section.

The first conventional T.O.C. ran in the March 22, 1969, issue. This version included all major departments, including fiction and poetry, and authors, as well as cover artists and cartoonists. According to Ben Yagoda’s book About Town (2000), when a longtime editor, Daniel Menaker, mentioned the new T.O.C. to a fact-checker at the magazine, the checker protested, “But now readers will know what’s in the magazine.”

In the April 18, 1988, issue, the magazine ran the first full-page T.O.C. with new type and layout; it was also the first T.O.C. to feature the current Eustace Tilley image above the index.

A greatly expanded T.O.C.–including titles, blurbs, and major illustrations and photographs as well as articles–debuted in the October 5, 1992, issue, which was then-editor Tina Brown’s first issue. The current T.O.C. was unveiled in the February 21 & 28, 2000, seventy-fifth anniversary issue, and it featured a new layout and red typeface for certain departments.

Q. During the Second World War, was there a special wartime edition of the magazine for soldiers?

Jon writes: From September 1943 through the end of 1946, The New Yorker produced a special overseas edition for the armed services, which was distributed free to soldiers by the Special Service Division of the U.S. Army. The “pony” edition, as it was known, began as a monthly, but became a weekly with the March 25, 1944, issue. Smaller in format than the regular magazine (its dimensions were 8 1/2 by 6 inches, and it usually ran to 26 pages), the pony New Yorker contained no advertising. It also omitted the Goings On About Town listings, and, with a few exceptions, movie, music, and theatre reviews. It did, however, replicate the typography and layout of the regular magazine. The entire Talk section was reproduced, along with numerous cartoons and a full page of Newsbreaks at the back. The pony also reprinted many longer pieces, including John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” which appeared in its entirety.

Credit has been given to the pony edition for the expansion of The New Yorker‘s readership after the war. Writing in the December 28, 1946, issue, E. B. White noted that it was the last issue that would be reproduced in a pony edition:

As near as we can make out from reports that have come in, the pony New Yorker was a success. Held together by only one staple, it was a quick disintegrator, but its fugitive little pages were studied by homesick men and women all over the uncivilized world…. The small type was calculated to destroy what was left of a soldier’s vision; nevertheless, the pony was hungrily read–some copies by a dozen or more people. At one time, what with the copies of the regular edition mailed second-hand by soldiers’ families, our service readers outnumbered our civilian readers ten to one. Thank God that is no longer the case, and thank God for the reason why it isn’t.

Addressed elsewhere in Ask the Librarians: VII: Who were the fiction editors?, Shouts & Murmurs history, Sloan Wilson, international beats; VI: Letters to the editor, On and Off the Avenue, is the cartoon editor the same as the cover editor and the art editor?, audio versions of the magazine, Lois Long and Tables for Two, the cover strap; V: E. B. White’s newsbreaks, Garrison Keillor and the Grand Ole Opry, Harold Ross remembrances, whimsical pseudonyms, the classic boardroom cartoon; IV: Terrence Malick, Pierre Le-Tan, TV criticism, the magazine’s indexes, tiny drawings, Fantasticks follies; III: Early editors, short-story rankings, Audax Minor, Talk’s political stance; II: Robert Day cartoons, where New Yorker readers are, obscure departments, The Complete New Yorker, the birth of the TOC, the Second World War “pony edition”; I: A. J. Liebling, Spots, office typewriters, Trillin on food, the magazine’s first movie review, cartoon fact checking.