Martin Schneider writes:

In the mid-1990s, an artist friend gave me his well-thumbed hardback copy of Negative Space. It was one of the better presents I’ve received. What a good critic. He will be missed.

Author Archives: Emdashes

I’m Back

Report: Canada remains superb in all ways. I’m delighted to see all the swell posts created in my absence; sometimes it’s nice not to be needed!

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic By Paul Morris: Karma Chameleon

Here’s Paul on today’s politically minded cartoon (click to enlarge):

“The Chameleon,” David Grann’s recent New Yorker story about con man Frédéric Bourdin, inspired this cartoon, as did the tragic and dangerous situation in South Ossetia. And yup, that’s S. Ossetia’s de facto flag.

More by Paul Morris: Enter our exciting contest to name the upside-down question-mark! Entries accepted until August 25. Plus, “The Wavy Rule” archive; “Arnjuice,” a wistful, funny webcomic; a smorgasbord of multimedia at Flickr; and beautifully off-kilter cartoon collections for sale and free download at Lulu.

Finally, a Literary Event Involving Pigeons!

Martin Schneider writes:

Longtime readers will know that this blog looks kindly on the noble rock dove, otherwise known as the pigeon.

On Monday, August 18, at 7 pm, McNally Jackson Books hosts a reading by Courtney Humphries, author of Superdove: How the Pigeon Took Manhattan and the World.

The book has an amusing cover (click to enlarge):

McNally Jackson Books is located at 52 Prince Street.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Billow Fight

Today, Paul contemplates the impending revival of damp pleats. On a related note, how big is steampunk really? Does anyone know? Tell us in comments! We’re a bit a skeptical here. As always, click to enlarge.

More by Paul Morris: Enter our exciting contest to name the upside-down question-mark! Entries accepted until August 25. Plus, “The Wavy Rule” archive; “Arnjuice,” a wistful, funny webcomic; a smorgasbord of multimedia at Flickr; and beautifully off-kilter cartoon collections for sale and free download at Lulu.

Man Loses Dog: A Metropolis Mourns

Chris Russo, known to many as “Mad Dog,” is leaving the tri-state-area sports behemoth WFAN, a move that brings the 19-year run of the afternoon sports radio talk show “Mike and the Mad Dog” to a sudden end. Right this minute, on the very last installment of the show, Mike (Francesa) is fielding a seemingly endless string of calls attesting to an importance that can only accrue in 330-minute installments five times a week over many years. I count myself as a fan.

Nick Paumgarten wrote about the curiously addictive duo in 2004; writing for ESPN.com’s “Page 2” in the spring of 2006, Bill Simmons also captured the singular appeal of the show.

Danza, Zogby, and Thom Yorke[r]: The Friday Intern Roundup

Each Friday, the Emdashes summer interns bring us the news from the ultimate Rossosphere: the blogs and podcasts at newyorker.com. Here’s this week’s report.

Sarah Arkebauer

The Cartoon Lounge was brimming with gems this week. Zachary Kanin continued his Sandwich Duel with a fourth installment, this one featuring Tony Danza. Chris Onstad fired back with his own endorsement—from Mick Jagger. I was delighted to see that Kanin interviewed Josh Fruhlinger, the man behind the Comics Curmudgeon, which is one of my favorite blogs. [You’re not alone! —Ed.] Since I read Mary Worth, Rex Morgan, M.D., and Apartment 3-G daily, I couldn’t have been happier to see Kanin post not just one but two of his own soap-opera strips. I can assure you that they’re fresher and funnier than the newspaper soaps.

The Book Bench this week included a thoughtful remembrance of Mahmoud Darwish. The post contains a hauntingly charming excerpt from his poem “Remainder of a Life,” which The New Yorker published in 2007. This week’s posts also included a scintillating “In the News” feature in which I discovered provocative tidbits about nursing home patrons, Guitar Hero, and Gordon Brown. I also enjoyed the treasure trove of fun facts in the post about pollster John Zogby’s new book.

Goings On posted eloquent memorials of Bernie Mac and Isaac Hayes. Both posts include thoughtful insights on their careers and characteristic video clips. The blog also put up two rather bizarre posts. One is an examination of the food it takes to fuel Super-Olympian (and my current personal hero) Michael Phelps; the sheer amount of food he eats every day is unbelievable (especially since he doesn’t cook). The second bizarre piece posted was a report on Pascal Henry, the man who disappeared while eating his way through every Michelin 3-star restaurant in Europe.

I got a surprise this week from The Rest is Noise: Alex Ross offered some insights on the Olympic opening ceremonies. I hope he permanently returns from summer hiatus soon!

I was excited to see a new Fiction Podcast up for August this week. The post is of Jeffrey Eugenides reading Harold Brodkey’s short story “Spring Fugue.” I wasn’t very familiar with Brodkey before listening to the podcast, but I liked what I heard. Even though spring is far away, Brodkey’s crackling descriptions of allergies and love and other springtime tropes felt close and familiar.

Adam Shoemaker

This week in “Notes on politics, mostly”, Hendrik Hertzberg takes umbrage at a respectable publishing house’s willingness to put forth a less than respectable attack on Barack Obama. He also shares the latest McCain attack ad and suggests that the Republican contender (as well as the other fogies of American politics) are in a snit because the junior senator from Illinois has made them seem, well, uncool. Two more McCain moves that have Hertzberg upset: drilling (he thinks it would merely be a drop in the bucket—but that we have to pay for the bucket) and a clever little move we might call the preemptive “not playing the race card” approach.

Sasha Frere-Jones considers the state of the bass guitar, and tallies up the possible causes of its recent marginalization; he also shares his observations on Thom Yorke’s “new rave moves.” This Radiohead fan was glad to hear that its lead singer has moved on from the neck bashing of a few years hence, which surely verged on vertebrate-snapping. Last Friday, Frere-Jones, in a list-making mood, offered readers a list of musical events organized by his predicted reception, from “Robust, Calm Happiness” to “Hiring People to Throw Themselves in Front of These Things So They Don’t Accidentally Brush Against Me.”

George Packer didn’t write anything this week in “Interesting Times.” A year ago, though, he wrote Karl Rove’s epitaph, an act that, despite the Bush advisor’s resignation that week, might have been a bit premature. Packer’s prediction was right, though, and now that the “Boy Genius” has been reduced to mere punditry, I wonder whether Packer would maintain that his statement then, that “the Rove approach to governing helped lose Iraq,” still applies, or if hope has sprung in the year since his demise—a development that might be described by Rove’s other nickname.

I also dug into the archives of New Yorker Out Loud this week to indulge myself in Matt Dellinger’s interview with Burkhard Bilger back in April, when the magazine published Bilger’s article on Art Rosenbaum and Lance Ledbetter’s quest to hunt down the last of Southern folk music. It was this piece that inspired me to purchase Goodbye Bablyon this summer, whose nailed wooden box—stuffed with raw cotton—and old-timey typography helps illustrate the strangely seductive power of the “authentic,” on which Bilger muses in the interview. He claims, and I believe it, that although few people pick up gems like Goodbye Babylon and The Art of Field Recording, those who do invariably want to start making music themselves. I’m thinking I’ll start with a banjo—or maybe an mbira.

Last but not least, The Borowitz Report manages to conjure up two of our potent Sino-fears: Chinese lead paint and allegations of the country’s duplicitous Olympic committee. The gold medals, Andy Borowitz reports, have been found to have high lead content. Normally I’d have no reason to doubt Mr. Borowitz. But, writing as I am from China, I can’t help but note the medal count. One would hope that this rising Olympic power might be a little more careful not to poison its own, especially considering the effects of lead on young children.

Previous intern roundups: the August 8 report; the August 1 report; the July 25 report; the July 18 report; the July 11 report.

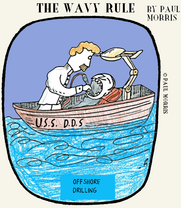

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Wave of Irrigation

Today the artist cops to a flight of fancy, based on a term that’s much in the news lately. (“Irrigation” is the term for what you do when the dentist asks you to spit.) Click to enlarge!

More by Paul Morris: Enter our exciting contest to name the upside-down question-mark! Entries accepted until August 25. Plus, “The Wavy Rule” archive; “Arnjuice,” a wistful, funny webcomic; a smorgasbord of multimedia at Flickr; and beautifully off-kilter cartoon collections for sale and free download at Lulu.

Shirley Jackson on Not Getting It

The Poynter Institute’s blog on journalism published “an interesting column”:http://www.poynter.org/column.asp?id=78&aid=146828 by Roy Peter Clark last month on the hazards of satire. The column’s real topic had to do with the infamous Obama cover, but contained some fascinating material from Shirley Jackson on responses from New Yorker readers to her story, “The Lottery,” whose “60th anniversary “:http://emdashes.com/2008/07/happy-belated-60th-anniversary.php of publication was just the other day.

From Clark’s column:

[Jackson’s] essay called “Biography of a Story” begins this way: “On the morning of June 28, 1948, I walked down to the post office in our little Vermont town to pick up the mail. … I opened the box, took out a couple of bills and a letter or two, talked to the postmaster for a few minutes, and left, never supposing that it was the last time for months that I was to pick up the mail without an active feeling of panic. … It was not my first published story, nor my last, but I have been assured over and over that if it had been the only story I ever wrote or published, there would be people who would not forget my name.”

The column goes on from there, and makes for hair-raising reading for anyone who has faith in the intelligence of the average reader. (But see Paul Morris’ vision of what her story would’ve looked like it if it had gone through rewrite today.)

51 Years of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

I admit it: I always thought “Ruth Prawer Jhabvala”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruth_Prawer_Jhabvala was born in India (she wasn’t; she was born in Germany to Jewish parents). Nor did I realize she was the primary scriptwriter for Merchant Ivory Productions. And while we’re at it, I may as well ‘fess up and say that I never read anything she wrote before “The Teacher” appeared in the July 28, 2008 issue of The New Yorker.

To atone (at least a little), after reading “The Teacher,” I went back and read “The Interview,” Jhabvala’s first-ever story in TNY, which appeared almost exactly 51 years ago, in the July 27, 1957 issue. (Telling for the time, though, she signed it, “R. Prawer Jhabvala.”) And what interesting bookends these two stories make!

The narrator of “The Interview” is chronically unemployed and looking to stay that way. He is the sweet, good-looking, younger brother of his family, which is based in Bombay, I think. His older brother supports the family with a government job; his brother’s beautiful wife now runs the household; his mother is in her dotage; and his own wife, whose stupidity and ugliness he laments, wishes he’d get a job so that the two of them and their child will be able to move out on their own.

But the narrator has no desire to leave the rest of the family. Nor does he want to get a job: he’s had at least one before, which did not end well; he’s terribly afraid he will make mistakes and be yelled at. Far better, he reasons, to sit and think and let his family coddle him, because he is, he insists to the reader, a sensitive man.

The story’s poignance and the narrator’s weakness of character are perfectly encapsulated as the story comes to a close. The narrator, despite his position as a favorite in the family, is profoundly dissatisfied—and so, he notes, is everyone around him. First he describes his wife’s unhappiness, and then he goes on to describe that of the others:

bq. … my brother, who has a job, but is frightened that he will lose it—and my mother, who is so old that she can only sit on the floor and stroke her pieces of cloth—and my sister-in-law, who is warm and strong and does not care for her husband. Yet life could be so different. When I go to the cinema and hear the beautiful songs they sing, I know how different it could be, and also sometimes when I sit alone and think my thoughts, I have a feeling that everything could be truly beautiful.

Reading that, it’s hard not to feel that the narrator’s anguished passivity is central to the unhappiness of the other members of his family … and he knows it.

Fifty-one years later, in “The Teacher,” Jhabvala writes about Dr. Chacko, who, though hardly anguished, could be an older, stronger, happier version of the narrator of “The Interview”. Like him, Chacko is charismatic—people dote on him, and give him lodging, food, and employment, so that he never lacks—and he, too, is passive. He simply accepts what people give him until they stop giving.

When we meet him, he is teaching an informal workshop in New York on a regular basis. In the course of the story, a disillusioned adherent breaks with him publicly, and the workshops come to an end. Later, the narrator asks him about it.

He said, “People move on. I move on, too.” As he did so often, he answered my question before I had asked it. “There’s always somewhere. One gets used to it.”

I said, “But wouldn’t you rather stay?”

“If there are people who wish me to stay.”

Evidently, he didn’t intend to continue this conversation, and I also realized that there was no need. It was cool outside now, in the night air. Glowworms glittered below, stars above. Instead of talking, he began to hum one of his songs. Was this his teaching? To say nothing? To want and need nothing?

So we see that Chacko’s passivity is different from that of the narrator of “The Interview,” because it has a spiritual dimension—or that’s how others perceive it, at any rate. It’s this perception that makes people want to give him food, lodging, and adulation. The irony is that it’s never clear what he teaches and writes about, though it has to do with “life and death” (which is obviously supposed to be Significant). In fact, it’s not even clear whether Chacko himself understands what he’s trying to teach.

But Chacko’s passivity is not the only point of similarity between “The Interview” and “The Teacher.” Both stories are characterized by pellucid sentences that I imagine are Jhabvala’s trademark; both are written in the first person; and the narrators (both unnamed) each persist in emotional stasis, victimized, sort of, by divorce and marriage respectively.

When we meet her, the female narrator of “The Teacher” has been divorced for 10 years and now lives in a large house outside of New York City. A pair of do-gooder acquaintances convince her to host Dr. Chacko in a cottage located on the grounds surrounding her home for what turns out to be a couple of years. She develops a mild, slow-growing, attraction to him that borders on the non-existent before finally, too late, it fluoresces into visibility. Just then, he betrays her in a minor way that might or might not be educational, but the do-gooders bring lots of orphans and “fugitives from bad homes” to fill the cottage rather improbably with the joys of childhood, and her life continues on, happily enough, though tinged with rue.

Oddly enough (though anyone reading TNY fiction on a regular basis this year, as I have, could have predicted it), she is detached and passive, like Chacko and “The Interview’s” narrator. When the do-gooders suggest she allow a stranger (Chacko) to move into the cottage, she goes along. When they ask her to give her the names of well-off acquaintances from which to request money, she complies. When they ask her to pay for the publication of Chacko’s turgid, and otherwise unpublishable tome, she writes a check.

She’s made powerless by … what? Her loneliness? It’s not entirely clear. But if so, then in her unhappiness, she is much more reminiscent of “The Interview’s” narrator than Chacko is. While she’s not the source of anyone’s unhappiness (if you don’t count one of the do-gooders, who’s a bit unbalanced anyway), she’s just as trapped by her passivity.

So: we have two stories set on two different continents and published 51 years apart that revolve around the same character, the same predicament. What surprising consistency!

I’d have to read more of Jhabvala’s work to see whether these bookends give a distorted view of her work. Probably they do; I hope they do. Still, I can’t help but wonder: should I be impressed by the high quality of Jhabvala’s work in 1957, or weep for her apparent lack of progression?

Perhaps an Emdashes reader knows …