Emily Gordon quotes:

“The whole blogger versus journalist debate that might have existed around 2004 is dead. Over. Stale. Uninteresting. I couldn’t care less — it’s a meaningless debate to have. What’s more interesting to me is what a blog means now.”

–Sewell Chan, from “So What Do You Do, Sewell Chan, New York Times City Room Bureau Chief?” (MediaBistro)

Author Archives: Emdashes

Spectral Appearances: An Arlen is Haunting The New Yorker

Martin Schneider writes:

In my best stentorian anchorman’s voice, I can honestly write that Senator Arlen Specter “rocked the political world today” when he announced that he would switch his party affiliation from Republican to Democrat, ensuring the Democrat’s a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate once Al Franken is seated sometime in June (it looks like). Specter is truly the man of the president’s 100th day.

When he was district attorney of Philadelphia, Arlen Specter was quoted in The New Yorker in opposition to the new Miranda rule. It was the December 14, 1968, issue. Since then he has appeared in the magazine’s pages many times—and there’ll be plenty more in the near future.

(Note that “Fight on the Right,” by Philip Gourevitch, and “Killing Habeas Corpus,” by Jeffrey Toobin, are actually about Specter, rather than merely mentioning him in passing.)

Here’s the full list:

“The Turning Point,” Richard Harris, December 14, 1968

Comment, Garrison Keillor, August 20, 1990

Comment, Adam Gopnik, October 28, 1991

Comment, Josselyn Simpson, August 3, 1992

“The Ogre’s Tale,” Peter J. Boyer, April 4, 1994

“Flat-Tax Follies,” Warren St. John, June 5, 1995

“The Western Front,” Sidney Blumenthal, June 5, 1995

“Ghost in the Machine,” Sidney Blumenthal, October 2, 1995

“Speaker of the Casino,” Sara Mosle, November 13, 1995

“The Stranger, Mary Anne Weaver, November 13, 1995

“Advice and Dissent,” Jeffrey Toobin, May 26, 2003

“Fight on the Right,” Philip Gourevitch, April 12, 2004

“The Candidate,” William Finnegan, May 31, 2004

“Hollywood Science,” Connie Bruck, October 18, 2004

“Blowing Up the Senate,” Jeffrey Toobin, March 7, 2005

“Ups and Downs,” Hendrik Hertzberg, November 14, 2005

“Unanswered Questions,” Jeffrey Toobin, January 23, 2006

“Hearts and Brains,” Hendrik Hertzberg, November 6, 2006

“The Art of Testifying,” Janet Malcolm, March 13, 2006

“Killing Habeas Corpus,” Jeffrey Toobin, December 4, 2006

“The Spymaster,” Lawrence Wright, January 21, 2008

“State Secrets,” Patrick Radden Keefe, April 28, 2008

“The Dirty Trickster,” Jeffrey Toobin, June 2, 2008

“The Gatekeeper,” Ryan Lizza, March 2, 2009

Fighting the Plague of Our Time: the Ban Comic Sans Movement

_Pollux writes_:

One reads alarming statistics sometimes. The “increase”:http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/04/20/090420fa_fact_bilger in the number of gigantic Burmese pythons in Florida, the growing rate of sea-ice shrinkage, the country’s unemployment rate.

Here’s another statistic that will chill your blood: by approximately 2018, usage of the “Comic Sans font”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comic_sans will have surpassed usage of the Helvetica and Times New Roman fonts. By 2030, Comic Sans will be the only remaining font. All other fonts will be extinct and will go the way of grunge and post-grunge lettering.

These are the statistics provided by the “Ban Comic Sans movement”:http://www.bancomicsans.com/about.html, which has sprung up in reaction to the Comic Sans typeface, originally designed by “Vincent Connare.”:http://www.connare.com Connare, as reported in this “_Wall Street Journal_ article”:http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123992364819927171.html by Emily Fleet, is not exactly against the movement against his typographic baby, and is certainly fonder of one of his other creations, the “Magpie font.”:http://www.connare.com/type.htm

Originally designed in 1994, Comic Sans has become the _bête noire_ of the typography world but “sometimes it has been a superhero, as seen in this humorous video,”:http://www.collegehumor.com/video:1823766 and sometimes a “dim-witted creature with a lisp.”:http://www.sheldoncomics.com/archive/070510.html

Holly Sliger and Dave Combs, the husband-and-wife team who started the Ban Comic Sans movement and man the typographic barricades, offer merchandise, font alternatives, and oratory on their website to inspire us all:

“By banding together to eradicate this font from the face of the earth we strive to ensure that future generations will be liberated from this epidemic and never suffer this scourge that is the plague of our time.”

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Horse/Power

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

Tennis, Anyone? Budge, Cramm, Thurber, and the Nonexistent Mrs. Poos

Martin Schneider writes:

I noticed in Jay Jennings’s review of Marshall Jon Fisher’s A Terrible Splendor: Three Extraordinary Men, a World Poised for War, and the Greatest Tennis Match Ever Played, in the Wall Street Journal, that James Thurber is mentioned as “the tennis-besotted writer for The New Yorker magazine.” I didn’t know Thurber was such a tennis fan; does anyone know if the subject pops up much in the better-known Thurber collections?

The intersection of tennis and The New Yorker cannot but remind me of my father, who was a fan of both things for most of his life (Herbert Warren Wind was a particularly special byline). Furthermore, I remember him telling me about that particular match—Don Budge against Baron Gottfried von Cramm in 1937, a sort of tennis version of the second Joe Louis-Max Schmeling bout, which happened a year later (turns out, both Schmeling and von Cramm were good guys; the story of von Cramm’s life is especially interesting). The setting was Wimbledon, but the match was not a part of the well-known tournament; it was a Davis Cup semifinal.

Knowing a fair amount about the subject but not about the book, I feel confident in recommending it anyway. The book apparently omits an amusing story connected with the match that my dad used to tell. Here it is, quoted from Budge’s memoir (I found it here):

I know I was still in a daze in the locker room. It was as if everyone was trying to outdo each other in congratulating me. Tilden came in, and it was right then that he came over and told me it was the greatest tennis match ever played. Others had about the same thing to say as Tilden did—everyone, that is, except Jack Benny. He came in with Lukas an Sullivan, and while they were raving on at length, Benny just shook my hand and mumbled something like “nice match,” as if I had just won the second round of the mixed doubles at the club. I remember, Jack Benny was the only calm person in the whole locker room. The place was like a madhouse.

[snip]

After I won at First Hills, I went out to Los Angeles to play the Pacific Southwest Tournament. After my first-round match there, which was a rather normal, unexciting one, I looked up from my locker, and who should be coming at me but Jack Benny. He was positively beside himself, hardly pausing to say hello before he launched into a babbling, endless dissertation on how wonderful, how exciting, how fantastic the Cramm match had been. It was like one of those scenes from his show. I would keep trying to interrupt him, unsuccessfully. “But Jack”—I would try to start. And he would go right on.

“Magnificent, Don. It was just marvelous. Why when you—it was incredible. And then you—why, I’ve told everybody about it.” And on he went.

“But Jack,” I kept on, so that at last he stopped long enough to take that pose he is famous for, the palm cupped on his cheek, staring at me curiously. “Jack, I don’t understand,” I began. “At Wimbledon, after the Cramm match, you were the only person I met who was relaxed and calm. Now you carry on like this. The match was two months ago. Then you were unmoved. Now you’re jumping around all excited. What is it?”

“Don,” he said. “The truth is, that the Cramm match was the first tennis I ever saw. Now since then I’ve seen others, but at the time I thought all matches were more or less like that.”

I decided to search Thurber’s New Yorker contributions for tennis references, and found a silly and slight short story called “This Little Kitty Stayed Cool.” I can’t improve on the abstract:

Tells of girl who is an excellent tennis player. Her name is Kitty Carraway. A man by the name of Poos is proposing to her, but she doesn’t like the name Poos and refused. It just doesn’t sound as nice as Kitty Carraway. Argument.

Frankie Manning, Dance Legend, 1914-2009

-thumb-182x136.jpg)

Farewell to a radiant human being, a breathtaking performer, a great teacher, a jazz innovator, and the inspiration to untold numbers of swing and other dancers around the world.

This remarkable photo of Frankie, taken (most likely) last year, is by Holly Van Voast and is used with permission.

Later: That weekend was a long and lindy-hopping celebration of Frankie’s life and exuberant self.

Thursday: See Jonathan Safran Foer Interview Zadie Smith

A friend passes on information:

Acclaimed British writer Zadie Smith’s first book, White Teeth, won a number of awards, including the Guardian First Book Award and the Whitbread First Novel Award. Smith’s second novel, The Autograph Man, won the 2003 Jewish Quarterly Literary Prize for Fiction. On Beauty was published in 2005, and won the 2006 Orange Prize for Fiction.

Jonathan Safran Foer is the best-selling author of Everything Is Illuminated, which won numerous awards, including the Koret Award for best work of Jewish fiction of the decade, and, like White Teeth, the Guardian First Book Award. His second novel, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, was a finalist for the IMPAC Prize. Foer joined the NYU Creative Writing Program faculty in 2008, and lives in Brooklyn,

New York.

Date: Thursday, April 30th, 7:00 p.m.

Location: Tishman Auditorium, Vanderbilt Hall, 40 Washington Square South

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Crazy Ivans

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

New Yorker Covering “Swine Flu” Story since the Ford Administration

Martin Schneider writes:

Credit Twitter users supergork and echidnapi with the catch.

In the May 31, 1976, edition of The New Yorker, there appeared a “casual” (what today would be filed under “Shouts & Murmurs”) by Richard Leibmann-Smith satirizing the hullabaloo surrounding awards ceremonies. Leibmann-Smith spent page 31 (subscribers only) musing on the following scenario: what if the “Academy” in “Academy Awards” signified the American Academy of Medicine? What if there were a “Jonas” instead of an “Oscar,” with the categories Best Disease, Best Symptoms, Best Virus, and Best Potential Epidemic? Riffing on the most recent Oscar winner, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which had also effected a sweep of all the major categories just two months earlier, Leibmann-Smith chose as his awards juggernaut “Swine flu,” as in the piece’s title (prepare wince reflex), “Swine Flu Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

On the intersection of Twitter and swine flu, Randall Munroe expresses more amusingly something I had noticed as well.

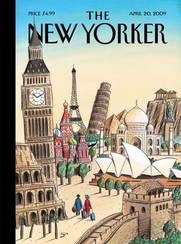

Sempé Fi (On Covers): Journey’s End

Pollux writes:

A collection of world monuments grace the cover of the April 20, 2009, issue of The New Yorker. These are the landmarks you have to see before you die—or at least, that’s what people say. It may be that one becomes reincarnated as a docent at the Taj Mahal or a Qualified, Talented, Experienced, Enthusiastic, Friendly employee of Walking Tours of Pisa, thus making your travels in this lifetime pointless.

Despite the world’s construction efforts and fervid competition between nations, the list of famous world landmarks has remained fairly standard over the past half-century or so. New buildings and structures have not supplanted Big Ben, the Eiffel Tower, and the Statue of Liberty. The London Eye has not become the landmark most associated with London.

In Italy, efforts to recreate the “Bilbao Effect,” the economic boom that occurred after the building of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in that Basque city, have produced exciting, interesting buildings (Renzo Piano’s Parco della Musica; Richard Meier’s Jubilee Church; Meier’s Ara Pacis Museum), none of which are instantly recognizable landmarks, although we can judge Berlusconi’s Ego to be a recognizable Italian landmark.

China, despite gargantuan Olympic efforts, still relies on that ancient but great Wall to the north, as ineffective against marauding Mongolians in centuries past as it is effective at pulling in tourists.

Jacques de Loustal, who is, according to his website, a fan of the Fauvists, here holds back from the vivid coloring that characterizes his work and that of the Fauvist movement. His New Yorker cover is almost lugubrious, as if he were expressing the fact that all of the challenges and adventures associated with traveling are gone. Gone are the strong reds and bright blues that usually characterize his work.

His cover, entitled “Ultimate Destination,” is ultimately an exercise in sobriety, displaying little of the playfulness seen in his other travel-themed cover for The New Yorker, for example, which depicted two travelers dressed for a hard winter strolling across an exotic, subtropical beach.

“How do you see these trees? They are yellow,” Gauguin once advised. “So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion.” De Loustal puts in none of these. Perhaps it is intentional. All travel requires these days is a stroll in a graveyard of monuments, where we’re immunized from “real life” in Russia, China, or Australia, for example. Perhaps we are all traveling gnomes when we travel, and all we require is to have our picture taken in front of a landmark. And then we move on. We have conquered and landmark-spotted the monuments on our list, and now we can ignore the country and the routes that surround them.

The famous monuments have been transplanted for the benefit of two well-dressed travelers, who drag Samsonites down an unmarked and lonely route. The Statue of Liberty shares the same Loustalian waterway with a Venetian gondola, while the Parthenon looks over both. The Leaning Tower of Pisa tilts perilously close to the Pyramids while the Eiffel Tower remains as ramrod straight as a 1,000-foot baguette.

The world is flatter and the world is smaller. In this shrunken world of ours, it is possible to get a picture taken in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral and the next day find oneself at the Sydney Opera House’s gift shop, located in the lower concourse of that New South Wales landmark. You’ll be exhausted, of course, which will explain your purchase of a box of authentic tile fragments collected during the building’s original construction and sold for 135 Australian dollars.

As the Spanish say, “el mundo es un pañuelo“—”the world is a handkerchief,” and the world has become more a single ultimate destination devoid of context than a series of diverse, disparate locations.