Martin Schneider writes:

Emily and I generally have little patience with the apparent hordes of pedants who seem just a tad too delighted when the come upon an occasional factual error in The New Yorker. (N.B.: As a copyeditor, my job description is basically “professional pedant,” so don’t take that slam too much to heart.)

Putting out a magazine is hard, as Emily knows all too well and I’ve also been able to figure out over the years, and the belief that The New Yorker might possibly (or ever did) achieve pristine perfection with regard to facts is kind of the adult version of believing in the tooth fairy. Magazines have deadlines; facts are elusive; brains get tired; it’s hard.

And yet, and yet—this position, in a sense, allows The New Yorker to benefit from its outsize reputation as the Magazine That Never Errs while shielding it from the responsibilities that that status brings with it.

So, you know, yeah—The New Yorker shouldn’t ever depart from its implied mission to Get It All Right, which mission (and a sizable budget) allows it to publish a great deal of material on a vast range of subjects with what everyone would agree is a dauntingly high degree of accuracy. That’s the story here, not that it got the identity of the 1953 Cy Young Award winner wrong that one time (or whatever).

We get a fair number of people writing in, alerting us to this or that inaccuracy, and we tend to ignore them (fair warning). But recently a fellow named Craig Fehrman contacted us, inquiring about a possible link to an article he had written about a recent error in The New Yorker.

I admit I indulged in a preemptive wince. And actually, I’m not entirely sure that the article doesn’t share just a bit of the same mindset as the “mere” error-flaggers out there in the magazine’s audience. But his article so transcends that big-brained delight in catching someone out, I thought it would be worth linking to it.

So here it is: “Just The Facts at The New Yorker?” by Craig Fehrman, at Splice Today. I particularly liked his closing point, about The New Yorker‘s subtle and precarious existence between print and the Internet.

While we’re at it, a couple of additional fact-checking links. Andrew Hearst at the indispensible Panopticon blog, posted a big chunk of “Are You Completely Bald?” a 1988 New Republic article by Ari Posner and Richard Blow a few years ago.

Fehrman links to John McPhee’s reminiscence from earlier this year about fact-checking as well as an amusing Wikipedia list (loooove those Wikipedia lists) called “Prominent former fact-checkers” which verifies that fact-checking can be the first step in a noteworthy career, but only in a narrow set of egghead-y endeavors. No NHL goaltender has ever started out as a fact-checker (apparently, anyway; I await the Wiki update).

Category Archives: Hit Parade

Potentially Controversial Observation Re: Buffalo Sentence

Martin Schneider writes:

Has anyone entertained the notion that perhaps “Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo” is not a valid English sentence?

If you are not aware of what I’m talking about, by all means head over to Wikipedia and catch up, it’s a marvel.

(Very quickly, because these things get complicated, if you imagine a (purely optional) comma after the fifth “buffalo,” you might glimpse a valid sentence that means something like, “Those NY-state bison that NY-state bison often bully, they also bully NY-state bison.”)

As far as I know, I believe that anyone who is able to follow the grammar of the sentence accepts the premise that the sentence is valid. That is to say, the set of people who deny its validity is congruent to the set of people who don’t get it. Seeing the argument for its validity is the same thing as accepting its validity.

I’m wondering if that’s really the case. Maybe you can see why it works, but also deny that it counts as a valid sentence. I’m going to throw it out there.

Before we continue, I must invoke the classic sentence devised by Noam Chomsky, “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously,” which serves to establish that a sentence can be grammatical while having a nonsensical semantic meaning (these words are cribbed directly from the Wikipedia entry on the sentence). I think I’m arguing that “Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo” might be a grammatical sentence without a valid semantic meaning—if that matters. I’m not sure it does matter, but it might.

In my “comprehensible” rendering of the sentence in the parenthetical above, I’m concerned about the insertion of the word “also,” which is, I think, conceptually necessary to make the sentence work, but also threatens the sentence’s validity. Can a purely tautological sentence be said to be valid?

The trouble is that the activities and entities involved are congruent. So the group of “buffalo from Buffalo” who buffalo “buffalo from Buffalo”—what is it they do, now? Oh yes. They buffalo “buffalo from Buffalo.”

But no: in order to avoid pure tautology, they do not merely “do that.” They also “do that.” It’s always phrased that way in the rendering, they “also” buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

As evidence, citing the Wikipedia page, here are two more ways to explain the sentence:

Bison from Buffalo, New York, who are intimidated by other bison in their community also happen to intimidate other bison in their community.

THE buffalo FROM Buffalo WHO ARE buffaloed BY buffalo FROM Buffalo ALSO buffalo THE buffalo FROM Buffalo.

Note that both examples take pains to include the word “also.” But you can’t “also” move from one activity to the same activity. Can you? Let’s see if it holds up in a different context:

My hamster, who enjoys lettuce, also enjoys lettuce.

Is that a valid sentence? I think it’s not clear.

Moving on. There’s a related problem, which is the absolute congruity of the groups “Buffalo buffalo.” I don’t really know if that set of animals truly can be said to bully … itself.

The sentence works if you think of it as describing a situation in which some Buffalo buffalo do something to some other Buffalo buffalo, as in the first example just cited: “Bison from Buffalo, New York, who are intimidated by other bison in their community also happen to intimidate other bison in their community” (emphasis mine). I’m just not sure that that’s what the words mean. Let’s try a test case:

New Yorkers root for New Yorkers, who in return root for New Yorkers.

Is there really a distinct subject and object there? I’m not sure there is. Is that describing two actions, or one action twice?

Now: it’s possible that the sentence means both things. It means something without semantic coherence, along the lines of my “New Yorkers” example, while also meaning something closer to “some buffalo do things to other buffalo.” Because humans and their brains are complicated and can read identical sentences with varying precision.

And maybe that ambiguity is all one requires to give the sentence semantic heft.

Thank you.

Of Pixels and Pastels: New Yorker artist Jorge Colombo’s iPhone Art

_Pollux writes_:

If you call “Jorge Colombo”:http://www.jorgecolombo.com/, he may not pick up.

He’s busy using his phone for something other than talking, e-mailing, and finding directions. He’s creating artwork with his iPhone, whose Brushes feature is a sophisticated “mobile painting” application complete with color wheel, undo/redo functionality, and a selection of brushes.

This is powerful technology, and the Portuguese-born Colombo applies an artist’s sensibility to create immensely delicate and interesting iSketches that capture the city in a new medium. The iPhone has become one more tool in the artist’s kit. “I got a phone in the beginning of February, and I immediately got the program so I could entertain myself,” Colombo “remarks.”:http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/tny/2009/05/jorge-colombo-iphone-cover.html

But Colombo’s art isn’t gimmicky ephemera, and his art is not, thankfully, trapped on his phone. The June 1, 2009 “_New Yorker_ cover”:http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/tny/2009/05/jorge-colombo-iphone-cover.html is in fact a Colombo iArtpiece. He is also selling 20×200 iPhone drawings “at 20 x 200.”:http://www.20×200.com/aaa/jorge-colombo/

Colombo, born in Lisbon in 1963, is not a greenhorn graphic designer or emerging artist (not that there’s anything wrong with that), but an established illustrator, filmmaker, and photographer, who has worked as art director for various Chicago, San Francisco, and New York magazines. He has books under his belt, including the photographic novel “”Of Big and of Small Love””:http://www.jorgecolombo.com/bsl/index1.htm (”Do Grande e do Pequeno Amor”), a work of half-photography and half-fiction writing. iPhone’a Brushes app, then, is for him a new and useful tool rather than a replacement for camera or pen.

Paul Éluard once remarked that “the poet is not he who is inspired but he who inspires.” In the same way, Colombo is a poet who, no doubt, will inspire a new market for iPhone-generated art.

**James Falconer** “reports”:http://www.intomobile.com/2009/05/25/iphone-and-brushes-app-used-to-create-june-1st-cover-art-for-the-new-yorker.html on this story, and includes an image of Colombo’s cover.

The **Knight Center** “covers Colombo’s new artwork.”:http://knightcenter.utexas.edu/blog/?q=en/node/4118

Colombo’s isn’t the only one: the “iPhone Art Flickr group.”:http://www.flickr.com/groups/brushes/

Report: Frank Rich, Jane Mayer at the 92nd St. Y

Martin Schneider writes:

To see New York Times columnist Frank Rich interview New Yorker reporter Jane Mayer about the Bush administration’s torture policies at the 92nd Street Y, as I did last Tuesday in the delightful company of Emily and Jonathan, is to experience (in the audience) a certain kind of informed liberal orthodoxy in its most undiluted form. At times I felt that if we were to concentrate any more intently, we might inadvertently summon the corporeal form of Keith Olbermann, if not I.F. Stone himself.

As it happened, it was that degree of obvious advocacy and affection in the audience that permitted the conversation to be as focused, and yet as unfussy, as it was. In other words, Mayer and Rich scarcely had to adjust their dialogue to the audience—we were all on the same page. Rich wanted Mayer to explain what was happening with the torture story, and that’s exactly what she did. We were along for the ride.

Mayer’s latest book, The Dark Side, is now out in paperback. She is certainly one of the best-informed people in the country (not on a government payroll) when it comes to our government’s recent rendition and torture practices. She confessed a desire to investigate some new story, but as the facts of this one are not yet out, she keeps getting drawn back in.

On Obama, Mayer ventured a familiar combination of hope and incipient disappointment. Rhetorically Obama has been so good on the subject that it’s difficult to assess the obvious backsliding. The Bush administration left behind an intractable legal problem—how to prosecute dangerous members of Al Qaeda (almost certainly) whose rights have egregiously been violated and whose cases would surely be thrown out of court under any normal circumstances. As one CIA employee told her, “The problem was always the disposal plan.” The Obama administration clearly regards the matter of Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri, the subject of Mayer’s February 2009 article in The New Yorker, as a test case to see how this will play out, so keep your eye on that. On the subject of disposal, the Bush administration apparently contemplated with some seriousness a plan of putting the prisoners on a ship that would then circumnavigate the globe in perpetuity, an idea Rich instantly dubbed “Halliburton cruises.”

One interesting revelation was that journalists are not permitted to interview convicted terrorists—and they are also not permitted to interview people who for legal reason have had access to them, this “two degrees of separation” prophylactic approach bearing the bland appellation “special administrative measures.”

Mayer noted that there are detailed reports produced by the likes of the CIA’s inspector general and the Justice Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility that have yet to be released, an eventuality that is likely, in her view. So brace yourself for more shocking revelations. One of the tiny number of people permitted to see the interrogation transcripts called them the “the most disgusting thing he had ever seen.” Like any good reporter, Mayer takes the view that disclosure of these practices is essential to the maintenance of an open society.

Simplistic as it sounds, that process will yield heroes and villains. Doug Feith, David Addington, John Yoo, and their ilk are apparently “very nervous,” while others, like Alberto J. Mora, once general counsel of the United States Navy (as Mayer reported in 2006), distinguished themselves with their courage in opposing these reprehensible practices. Addington et al. prompt the question, were they imparting sound legal advice or did they have their collective thumb on the scale? The absence of an important 1983 waterboarding precedent in Yoo’s internal memoranda prompts the latter interpretation, an inauspicious sign.

One of the most interesting questions that remains is the degree to which the torture regime was a sincere effort to obtain valid intelligence or a cynical attempt to manufacture a justification for the war in Iraq. In my opinion, the available facts aren’t encouraging. If that manufacturing is exposed, it’s going to take a very long time for our country to come to terms with the official, costly duplicity in which our governmental representatives engaged.

The first question of the audience Q&A section demanded an impossible degree of information, albeit one close to the concerns of this blog: “Can you describe the process of writing a New Yorker piece from start to finish?” Mayer’s comments were appreciative yet betrayed a glimpse of the pressure that such high standards bring: “The process is endless, no one would believe it. . . . We have an in-house grammarian who will mark up your copy to the point that you want to cry—or change professions. . . . I have a hunch that it’s the typeface that makes us look so good.” She also singled out editor Daniel Zalewski for his unerring instincts.

There was more, but my hand can furtively scribble only so much, and the remainder of my markings are unintelligible, even to me.

Fighting the Plague of Our Time: the Ban Comic Sans Movement

_Pollux writes_:

One reads alarming statistics sometimes. The “increase”:http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/04/20/090420fa_fact_bilger in the number of gigantic Burmese pythons in Florida, the growing rate of sea-ice shrinkage, the country’s unemployment rate.

Here’s another statistic that will chill your blood: by approximately 2018, usage of the “Comic Sans font”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comic_sans will have surpassed usage of the Helvetica and Times New Roman fonts. By 2030, Comic Sans will be the only remaining font. All other fonts will be extinct and will go the way of grunge and post-grunge lettering.

These are the statistics provided by the “Ban Comic Sans movement”:http://www.bancomicsans.com/about.html, which has sprung up in reaction to the Comic Sans typeface, originally designed by “Vincent Connare.”:http://www.connare.com Connare, as reported in this “_Wall Street Journal_ article”:http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123992364819927171.html by Emily Fleet, is not exactly against the movement against his typographic baby, and is certainly fonder of one of his other creations, the “Magpie font.”:http://www.connare.com/type.htm

Originally designed in 1994, Comic Sans has become the _bête noire_ of the typography world but “sometimes it has been a superhero, as seen in this humorous video,”:http://www.collegehumor.com/video:1823766 and sometimes a “dim-witted creature with a lisp.”:http://www.sheldoncomics.com/archive/070510.html

Holly Sliger and Dave Combs, the husband-and-wife team who started the Ban Comic Sans movement and man the typographic barricades, offer merchandise, font alternatives, and oratory on their website to inspire us all:

“By banding together to eradicate this font from the face of the earth we strive to ensure that future generations will be liberated from this epidemic and never suffer this scourge that is the plague of our time.”

Lost & Never-Seen Thurber Cartoon: An Emdashes Discovery

Emily Gordon writes:

We invite you to click on the Thurber cartoon above to see it enlarged. By doing so, you will have been the first people in more than fifty years to ever see this cartoon, which has been lost in time. Until now.

It so happens to be April Fool’s Day, when your co-workers lace your latte with laxatives and French schoolchildren attach paper fish to one another’s backs–when companies from Google to BBC Radio 4 run elaborate hoaxes on their sites and servers.

But this is not a tradition at Emdashes, which, as much as its staff enjoys a good joke now and again (and some of us not at all), is a serious site with serious New Yorker-centric goals. We don’t mess around with certain things.

So ignore for a second that it is the first of April, and focus your attention on this! Emdashes has the distinct honor of coming into possession of a heretofore unpublished drawing by New Yorker cartoonist and writer James Thurber. As you know, I am an ardent fan of another classic New Yorker artist, Rea Irvin, and have conducted various investigations concerning the life and work of the magazine’s first art director.

As sometimes happens during the course of research at the New York Public Library, I stumbled across gems that I did not expect to find. One of them was a rare first edition of S. J. Perelman’s Pillowbiters or Not–and the other was an original Thurber drawing that I had never seen in any published anthology or collection, online or otherwise.

The drawing, yellowed with age, is vintage Thurber, both in style and substance. It dates perhaps to the early 1940s. No caption was attached, but a caption is unnecessary. The cartoons that Dorothy Parker famously referred to as having the “semblance of unbaked cookies” are works of art, instant collectors’ items, and like, well, a plate of freshly baked cookies to the millions of Thurberphiles around the globe.

The New York Public Library will forgive me for what I did next: I smuggled the newly discovered Thurber “unbaked cookie” in a manila folder marked “non-smuggled items” and went straight to my apartment to devise a cunning plan.

To wit, in exactly two weeks, on April 15, 2009, we will be holding an Emdashes Thurber Festival at the Wollman Rink in New York’s Central Park. We will be making high-quality, limited edition facsimiles of this untitled Thurber drawing available for sale for the incredibly (under the circumstances) low price of $15 and will also be offering, in honor of Thurber’s origins, authentic Ohioan cuisine: Cincinnati Crumblers, Toledo Butterscotch Flan, and Cleveland Cork ‘n’ Beans. Please join us in this celebration of an invaluable find!

Update, April 3: There is, of course, no S. J. Perelman book called Pillowbiters or Not. There are (perhaps regrettably) no such Ohioan specialties as Cincinnati Crumblers, Toledo Butterscotch Flan, or Cleveland Cork ‘n’ Beans. We have no plans for an Emdashes Thurber Festival, since Columbus’s own Thurber House and Museum has all such celebratory events well and humorously in hand. There are, alas, no uncatalogued Thurber drawings that I know of, but if there were, you can bet everyone at Emdashes H.Q. would run to buy the freshly printed collection. (At least The 13 Clocks was recently reprinted by New York Review Books, a windfall applauded by our friends at the New Haven Review).

Most obviously, I would never take anything from the New York Public Library but a renewed resolution that I should really get back to Tristram Shandy. The drawing above is a fond Thurber homage by our own Pollux, resident cartoonist; the post above, also a close but detectable facsimile, is by Pollux as well. And that’s it for another April Fool’s Day! Three cheers for James Thurber, who is a continual inspiration and one of the world’s unmatchable greats.

And for a nearly Thurber-era New Yorker wavy-ruled infographic about April Fool’s–as the abstract describes it, “A list of recent quaint practical jokes and their outcome, as chronicled in the daily press”–get thee to 1929 and the Digital Reader. Enjoy! —E.G.

Before Hersh and Mayer: Waterboarding Described in a 1946 New Yorker

Jonathan Taylor writes:

After reading Mark Danner’s New York Review of Books revelations and meditations on the Red Cross reports on Guantanamo, and trying to recapture some perspective on “torture”—what the word meant to all of us before it was associated on a daily basis with the United States first and foremost—I put the word into The New Yorker‘s search engine. The first thing I was reminded of was Lawrence Weschler’s 1980 two-parter on the use of torture under the Brazilian military dictatorship, “A Miracle, a Universe” (although these, of course, implicated the U.S., too). There’s also a lot on the subject relating to Nazi and Japanese World War II atrocities. Peter Kalischer’s 1947 story “Neighbor: Tokyo, 1947” describes an accused war criminal said to have forced “sick men to march up and down the damp stone corridors without their clothes”—the kind of thing that made Rummy chuckle.

But I also found a curious and disturbing story called “Police Duty,” by James A. Maxwell, from 1946, that the words of Red Cross report echo across the decades. The narrator describes a British policeman in Tripolitania (in Libya), his attitudes toward “Arabs,” and particularly an episode in which he elicits a confession from a suspected murderer.

Captain Westcott went over to the Arab and placed a hand on his shoulder. He asked several more questions in the same soft voice, but no sound came from the prisoner. Suddenly the Captain drove his right fist hard into the Arab’s stomach. The man gave a high cry and dropped to the floor, where he writhed, gagged, and gasped for breath. After a few moments, one of the guards jerked him to his feet, but he stood doubled up. My companions at the table looked at him as impersonally as if he were a stranger seated opposite them in a streetcar. Westcott came back to the table, poured a cup of tea for himself, and asked the Arab if he was ready to talk. The man said he knew nothing about the murder.

And, after an episode with a gruesome technique using “what looked like a pair of handcuffs,” described with clinical expertise by the narrator, produced no results,

Captain Westcott told one of the guards to get some water. When the policeman returned with two bottles of water, the prisoner was stretched out on the floor, face up, with one guard holding his feet and another on each of his arms. The guard with the water tipped the Arab’s head back and began to pour water down his nose. The man thrashed and gagged, and then retched. He was literally drowning. Wetcott told the men to stop. The guards pulled the man to his feet. He nodded his head when the Captain asked if he was ready to confess.

The story has all the chilling detachment of its abstract: “The policy of violence for violence is demonstrated….”

Who was James Maxwell? “Police Duty” and other New Yorker pieces (categorized Fiction) of his were collected in I Never Saw An Arab Like Him, published in 1948. He seems to have been a counterintelligence officer in the Middle East during World War II.

I haven’t found much about Maxwell or his book outside pay archives containing initial reviews of it. Commentary ran a review by Anatole Broyard; the free snippet on its site seems to herald a takedown:

As the land of technical genius, America has perfected millions of pleasure-giving, work-saving devices—smooth-riding cars, static-free radios, automatic washing machines, and so on indefinitely. It seems only natural then that Americans should have perfected a style of writing compatible with these mechanical conveniences—a style also mechanical, smooth, without static, full of devices, laundered of all distressing odors and smudges, etc.

Anybody know more about this Maxwell character? (Not to be confused with editor William Maxwell, of course.)

Norman Lewis’s Letters From a Vanished Spain

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Patrick French’s authorized biography of V.S. Naipaul, The World Is What It Is, will come out in the U.S. next month, complete with its salacious revelations of marital cruelty. After it was published in Britain in spring, the formidable Stephen Mitchelmore questioned the connection being hastily drawn between the writer’s vices and his books:

When I found out Naipaul was married, it was after I’d read and enjoyed the overtly autobiographical novel The Enigma of Arrival which does not (if a twenty-year-old memory serves) mention any other presence in the narrator’s Wiltshire cottage. Does this demonstrate a protective love or contemptuous indifference? Such is the ambiguity of writing.

Another new British bio, Semi-Invisible Man by Julian Evans, is not set for U.S. release. Like Naipaul, its subject, Norman Lewis, was a novelist and travel writer whose work appeared in The New Yorker. This work, too, turns on the writer’s sculpting of lived experience, switching, almost silently, between fiction and nonfiction as needed. An observation about Lewis in the Times Literary Supplement review of Semi-Invisible Man nicely illustrates the parallel. Lewis’s Voices of the Old Sea (1984) is a spare memoir of three summers he spent in an isolated Catalonian fishing village in the 1950s:

Lewis’s visits, we learn from the biography, were made in a large Buick, in the holidaying company of his partner of the the time and their children. You wouldn’t guess this from Voices of the Old Sea. Lewis was a secretive, contradictory man who nursed his inconsistencies because they fitted his understanding of how the world worked.

I haven’t gotten my hands on Semi-Invisible Man yet. But the UK reviews sent me to Voices of the Old Sea, and thence to some of Lewis’s New Yorker articles, mostly published in the 1950s and 60s.

Voices conjures the elemental traditional life of the village he called Farol, on the eve of its destruction by the tourist industry. This conquest was decades old by the time Lewis wrote the book. Farol’s residents were adamantly attached to a hardscrabble subsistence economy and a culture of atavistic paganism still not yielding completely to Catholicism, much less to anything called “Spain.” Their cosmology was dualistic: one world was Farol, the seaside, cat-infested village whose authority figures were fishermen. Its eternal Other was Sort, and inland, dog-riddled hamlet of cork farmers and other peasant landlubbers who wore shoes rather than rope sandals (chief among Farol’s superstitions was an abhorrence of leather).

As land and houses are bought up to build a hotel, a kind of suspense builds slowly, even though the final outcome seems obvious. And in fact it is shocking when suddenly the villagers, once dismissive of the possibility of change, cheerfully exterminate any private habit of life once the price became irresistible, to be replaced with something palatable to visitors’ expectations of Spain. It’s a sobering read for anyone historically minded who has been to the Costa Brava, or any other part of Europe extensively developed for tourism, and is tempted to think they have an eye for what is “authentic” to the place.

Lewis’s contemporary account of his sojourns in southern Spain, in a March 10, 1956, New Yorker “Letter from Ibiza,” has the same principal theme. He sought out Ibiza as he migrated “farther south each year to keep ahead of the tourist invasion.” Ibiza also exhibited a basic dichotomy between fisherman and peasant.

The existence of the generous, impoverished fisherman and that of the peasant, with its calculation and lacklustre security, are separated by a tremendous gulf. For a fisherman, to be condemned to plant, irrigate and reap, bound to the wheel of the seasons, his returns computable in advance to the peseta, is the most horrible of all fates.

However, the fisher and the farmer had in common their absolute faith in methods and customs that Lewis dated back to Roman, Carthaginian, and Arab rule over the island, equidistant between Iberia and Africa.

The Ibizan peasant is the product of changeless economic factors—a fertile soil, an unvarying climate, and an inexhaustible water supply from underground sources. These benefits have produced a trancelike routine of existence…. Much of the past is conserved in the husk of convention, and archaic usages govern his conduct toward all the crucial issues of life.

But already, Ibiza had a steady flow of transient bohemians and “modern remittance men—the free-lance writer who sees two or three of his pieces in print a year, and the painter who sells a canvas once in a blue moon.” And as in Catalonia, mass tourism was approaching, luring Ibiza’s fishermen into the unthinkable occupation of captaining boat excursions, and sometimes into trysts with “fair strangers.”

In Ibiza, Lewis describes this phenomenon almost whimsically; when he refers to the island’s “first cautious step forward into the full enlightenment of our times,” the undoubted irony is gentle. Similarly, in his October 15, 1955, New Yorker “Letter From Belize,” Lewis sees a “glamorized and air-conditioned Belize emerging as another Caribbean playground for the people of the industrial North” as a bona fide solution to the country’s economic problems, however unappealing it might be to the discriminating traveler. While alluding knowingly to the New Yorker reader’s distaste for “the chagrins of the tourist area,” he concludes with tips for “someone seized by weariness of the world” to retire in Belize, “Gaugin-style.”

But by the 1980s, Lewis had no remaining illusions about “the full enlightenment of our times.” His 1968 London Times article “Genocide in Brazil,” which exposed the oppression of Amazon peoples, had led to the founding of the tribal rights group Survival International. And in place of the little ironies facing the lucky discoverer of an “unspoiled” place, Voices of the Old Sea is a terse requiem. The beginning of tourist boat outings in Farol represent the collapse of the main pillar of the existing order, recorded with the bitter knowledge that there is now no traditional society that is not doomed, if it has not already disappeared.

Given how much Spain’s Costa Brava had changed already by the time Lewis was writing, Voices of the Old Sea is devastating in its understatement. Refraining from overtly referring to the full extent of the later transformation of the place, Lewis lets us fill in the blank sequel ourselves with the shocking knowledge we already have about our “enlightened” age. (I can only wonder what Lewis would have made of The New Yorker‘s other “Letter from Ibiza,” by Nick Paumgarten in 1998.)

Some differences between the article and the book point to the ways Lewis reshaped his experiences in order to bring out what he saw, in hindsight, as their ultimate meaning. An apparent allusion to Farol in the “Letter From Ibiza”—”my favorite Catalonian village”—gives it a “native population of a thousand,” and says 32 hotels had already been built. Without saying so explicitly, Voices of the Old Sea gives the impression of a village of perhaps a few dozen households, and the drama focuses on the creation of a single hotel, heightening the sense of nearness to extinction of the bearers of the old ways.

This misleading effect seems to amount to a clever method of omission, rather than an altering of the facts outright. But without the biography, I haven’t even succeeded in tracking Farol down to correlate his account to any known place. This epic blog comment is the most extensive discussion I’ve found about whether the village exists, or existed, under that name, or was perhaps a fictionalized place in which Lewis synthesized his area experiences.

Lewis’s longest New Yorker work was the 1964 serialization of his book on the Sicilian Mafia, The Honored Society. What keeps him interested in Sicily is the same thing as in Ibiza. The glittering history of an island, its Roman and Arab past seemingly concealed under a decrepit present, but to the lingering eye, actually revealed by it. The Mafia, he writes, is the descendant of an organization formed to defend the poor from the depredations of the Inquisition, which were more economic than theological. It eventually allied itself instead with the feudal landowning class, and after World War II, inhabited the shell of electoral politics (with the help of the U.S. military).

It is the same deadly combination of atavism and modernity that is also often Naipaul’s subject; the two also share a dazzling focus on its material manifestation in landscapes scarred by man. Joan Didion wrote in 1980 that for Naipaul, the world is “charged with what can only be described as a romantic view of reality, an almost unbearable tension between the idea and the physical fact.” The World Is What It Is, indeed. Or, as Lewis put it in the title of a memoir: The World, The World.

Like any other writer, a biographer is wrestling with “the tension between the idea and the physical fact.” French has the goods on “the physical fact”: Naipaul handed over his wife’s damning diaries, sight unseen, and The Guardian says they “take us probably as far as it is possible to go to the core of the creative process.” Andrew O’Hagan in the London Review of Books notes that in Semi-Invisible Man, Evans, who was Lewis’s editor and friend, reveals his misgivings about whether and how to use his own diary entries about a maritally sensitive incident. O’Hagan suggests the degree to which Evans grapples with “the idea,” in fact calling the book “an improvisation on the very idea of being Norman Lewis.”

In either case, it’s worth remembering that, however close we are getting to “the creative process,” it’s only through another’s creative process. I for one am looking forward as much to reading Evans’s book as French’s.

Special Guest Post: Revisiting John McPhee on NYC’s Greenmarkets

Our friend Jonathan Taylor writes:

I saw this news of a vendor ejected from New York City’s Greenmarket farmers markets, for offering products not raised on his own farm, just after I read John McPhee’s “Giving Good Weight,” an article on the markets from the July 3, 1978, New Yorker. (Not online; link is to abstract.) The Greenmarket program had only begun in 1976. McPhee worked for several months for Hodgson Farm of Newburgh, N.Y., manning stands (in “black Harlem,” Union Square, the Upper East Side and Brooklyn) and observing the initial interactions between farmers–who were new to selling on the streets of the city–and urbanites, who were often clueless about agriculture but, of course, were also finicky know-it-alls.

“Giving Good Weight” was reprinted in a 1979 book of the same title. Also in that volume is “Brigade de Cuisine,” a lengthy portrait (from the Feb. 19, 1979, issue) of a Tri-State-area country farmhouse restaurant so superb, and so happily off the Manhattanite radar, that McPhee insisted on concealing the real identities of the establishment and its chef, “Otto.” Farmers markets, and a restaurant said to be secretly the best table within 100 miles of Manhattan: both of these could be topics of articles you’d read in The New Yorker (or New York) today–but together, they suggest how the business of informed eating has changed over the past 30 years.

As described by McPhee, the early markets are recognizable, but differ from the epicenters of that brand of local and sustainable consumption that now defines the city’s aspirational food culture. McPhee glancingly notes just one “organic” producer, in quotation marks. Many of those first vendors came to the market as last-ditch effort to save a generations-old farm from ruin. The “grow-your-own” rule was in effect from the beginning, although then, at least, there was a provision for supplementing with small amounts of a “neighbor’s” crops.

McPhee saw the farmers–“friendly from the skin out, they are deep competitors”–accuse each other, sometimes even justly, of offenses that today would be more scandalous than Dines’s: acquiring produce trucked in to the Hunts Point Terminal in the Bronx, and passing it off as their own. But the growers and the Greenmarket organizers were still taking risks on each other in pursuing their common goal, the markets’ success; in this freewheeling atmosphere, a crate of California peaches earns only the stern, readily obeyed order from a Greenmarket official: “They must go back on the truck.”

The Greenmarket program was established in response to a situation in which “New Yorkers complained of brown lettuce and hard tomatoes while local farms went bankrupt,” in the program’s own words. In McPhee’s words, it provided “tumbling horns of fresh plenty at the people’s feet,” in something like an Old World market day, where the full spectrum of New Yorkers descended to drive a hard bargain. McPhee calls the Brooklyn market “the most cornucopian of all” and “a nexus of the race”:

Greeks. Italians. Russians. Finns. Haitians. Puerto Ricans. Nubians. Muslim women in veils of shocking pink. Sunnis in total black. Women in hiking shorts, with babies in their backpacks. Young Connecticut-looking pants-suit women…country Jamaicans, in loose dresses…white-bearded, black-bearded, split-bearded Jews. Down off Park Slope and Cobble Hill come the neo-bohemians, out of the money and into the arts.

When McPhee would arrive in the early morning hours at the lot, the Brooklyn market then occupied, at Atlantic and Fourth Avenues, “a miscellany of whores is calling it a day.” (The site, I believe, is now a P.C. Richard.)

Taken together, today’s markets probably offer up a similarly kaleidoscopic vision, although with 45 locations now, the stratification that McPhee observed between the Brooklyn “nexus of the race” and the 59th Street market (“Mucho white people,” another seller said) is even more advanced. For many customers’ dollars, markets compete not so much with the brown lettuce of bodegas, but with Whole Foods and pricey specialty stores. Much as I think market produce is worth every penny, I doubt I’ll ever hear, “How can you charge so little?” as McPhee did.

That dialogue between growers and customers is the meat, so to speak, of McPhee’s piece:

Woman says, “What is this stuff on these peaches?”

“It’s called fuzz.”

“It was on your peaches last week, too.”

“We don’t take it off. When you buy peaches in the store, the fuzz has been rubbed off.”

“Well, I never.”

Today, the repartee between the metropolitans and those who sustain them (and whom they sustain in turn) goes on; it’s more elaborate, now that the regulars are more preoccupied with the food they eat and how it came to be. Management consultant-turned-hot pepper and tomato grower Tim Stark describes, in the August issue of Gourmet (not online), the conversational duels he has to engage in with capsicum freaks and deeply skeptical West Indian women just to make a couple bucks’ sale. McPhee’s Hodgson Farm, by the way, is still at the Union Square market.

(Another fine account by a writer working a spell for a New York Greenmarket vendor–although on the farm rather than at the markets–is the one by poet and novelist James Lasdun‘s in the London Review of Books.)

“Brigade de Cuisine” is even more of a blast from the past, and I found it a bit embarrassing to read even before I found out what happened when the piece was published. The accolades that David Chang gets are nothing to McPhee’s opening pronunciation that meals at “Otto’s” resaurant would occupy the first “twenty or thirty” spots on his all-time list of best repasts–eventually followed, “perhaps,” by “the fields of Les Baux or the streets of Lyons.” (McPhee probably does have such a list; in 2007 he wrote in The New Yorker about his “life list” of the unusual foods he’s eaten.) This was taken as a brazen insult to the city’s restauranteurs, compounded by Otto’s dismissal of New York’s ranking French restaurants as “frog ponds.” (The magazine subsequently ran a note saying that Otto had “guessed wrong” when he suggested to McPhee that Lutece’s turbot was frozen.)

This Time article nicely describes the ensuing caper: New York Times critic Mimi Sheraton identified, and panned, Otto’s table within days. (Otto, a.k.a. Alan Lieb, had, by the time McPhee’s article came out, moved on to a new restaurant, the Bullhead Inn in Shohola, in northeastern Pennsylvania.) More details of the aftermath are in Sheraton’s memoir Eating My Words. She wrote that “many years later,” she “unwittingly” dined at Lieb’s subsequent restaurant in the Poconos, but gives no further details “because it is no longer of public interest.”

Reading “Brigade de Cuisine” today, it’s not hard to conclude that McPhee was too easily impressed, as he worshipfully recounts Otto’s every move: “His way of making coffee is to line a colander with a linen napkin and drip the coffee through the napkin.” McPhee invites the reader (in vain, in my case) to fantasize about being able to follow Otto around New York and imitate him: “With luck, you will be seated at a table near him. Listen. Watch. He orders spiedino. You order spiedino…. He orders a bottle of Verdicchio. You order a bottle of Verdicchio.”

Most of Otto’s actual cuisine sounds stuffy and old-fashioned (veal cordon bleu), standard (osso buco) or sometimes just unappetizing (“sauteed chicken breasts with apple-cider sauce”), rather than visionary. It conjures the obsolete mode of food appreciation that went by the name “gourmet,” a word that now sounds quaint in the “foodie” world that encompasses Thomas Keller and the Red Hook ballfields, Chowhound and Top Chef.

McPhee contrasts Otto’s restaurant with the industrialization of even somewhat upscale restaurants, visiting Idle Wild Farm Inc., a provider of frozen “instant entrees” to “kitchenless kitchens.” He implies that his desire to keep Otto’s identity secret is intended to protect the last of a dying breed: the restaurant where fresh, seasonal food is cooked carefully by a perfectionist chef for an intimate group of regular appreciants. But apart from the merits of his dishes, in this respect Otto’s enterprise seems a precursor to modern priorities rather than “the wave of the past,” as McPhee wrote. There are certainly as many factory-made entrees by the likes of Idle Wild being served, in casual-dining and hotel restaurants, as McPhee might have feared. But his description of Otto–whom another acolyte calls “the last great individualist”–reads in many ways like almost a parody of the archetypical hot New York chef of today.

It’s easy to say that with hindsight, but this points to what strikes me as a shortcoming in both pieces: a certain lack of perspective, a tunnel vision. Though McPhee is recording change–a new way of buying food in New York, a seeming decline in culinary craftsmanship–his writing here lacks, for me, enough of a sense of the specificity, the contingency of the moment: a sensibility found (if sometimes to a portentous fault) in the work of other great chroniclers like Joan Didion, George Trow, Renata Adler. McPhee’s especial drive to get into the thick of things, materially, might serve his writings on nature better than it does social subjects like this one. But it does preserve invaluable raw material for food anthropologists of New York, professional and amateur, and that’s satisfying nourishment.

Exciting Emdashes Contest! ¿What Should We Call the Upside-Down Question Mark?

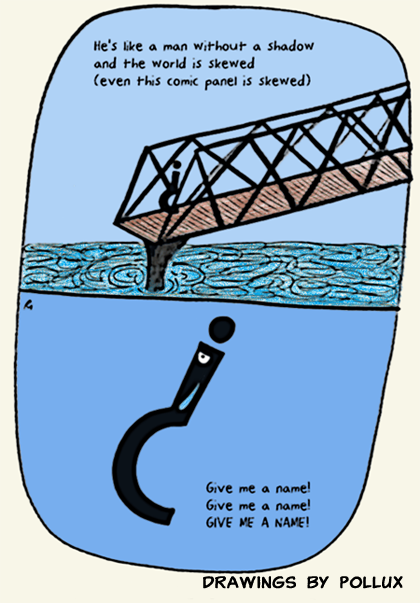

Above: A haunting dramatization of the dilemma in question. Click to enlarge.

The other day, Pollux, our “Wavy Rule” staff cartoonist, and I were questioning some punctuation: namely, the upside-down, Spanish-style question mark. After consulting friend and lettering expert Paul Shaw–who reports that “Bringhurst just calls it an inverted question mark, no special name”–we decided it was a real scandal that this character dare not speak its name. (Parenthetically, I wonder when the nameless mark will become a standard part of the computer keyboard, especially in America, where Spanish is rápidamente becoming our dual language?) So we decided to sponsor a contest. Paul wrote everything from here on–and, of course, drew the searing cartoon above.

You’ve seen it before. It stands on the west end of elegant Castilian questions: ¿Adónde vas? ¿Cuando llegarás? ¿Quien eres tú?

Ah, the upside-down question mark! Its limited range lends this punctuation mark a certain romantic air, its elegant curve bent and shaped by the same winds that propelled caravels and galleons on treasure runs across the ocean sea, its use first legislated in 1754 by a second edition of the volume OrtografÃa, issued by Spain’s Royal Academy.

You can make one yourself: hold your Alt key down, hit the number-lock key, and then type the numbers “168.” [On a Mac, just type option + shift + ?. –Ed.] There, you see it? It stands nobly, and a little sadly, on your computer screen–like a single tear on the face of a father who’s walking his daughter down the aisle of a church, or like a grandee who has been reduced to complete penury but who still points to his ancient coat of arms on the wall.

A noble punctuation mark, to be sure, but deficient in one regard: it lacks a name. “Upside-down question mark” is purely descriptive. Its Spanish name is equally lacking in punch: “signo de apertura de interrogación invertido.”

Now’s your chance to make history. Name this punctuation mark. Give it a name both euphonious and appropriate. Earn everlasting glory. Win a prize–dinner for two at the Spanish, Mexican, Ecuadorian, Dominican, &c., restaurant of your choice, or, if you prefer, a beautiful copy of Pablo Neruda’s immortal The Book of Questions. Emdashes wants to hear your best ideas, so post them in the comments or, if you’re shy (as so many of you are, we know and sympathize), just email us. All entries are due by August 25, no question about it. We are very much looking forward to your submissions. At TypeCon last week, I got two impressive entries from genuine maniac typophiles; I’ll post them in the comments as soon as things get rolling. The very best of luck to you, and andale!

And if you’d like to see more drawings by Pollux, check out “The Wavy Rule” archive.