_Pollux writes_:

In 1930, New York City, as described by the Spanish poet Federico GarcÃa Lorca, was inhabited by those “who lift their mountains of cement / where the hearts beat / inside forgotten little animals / and where all of us will fall / in the last feast of pneumatic drills.”

In 2009, New York’s mountains of cement are still rising, and we have yet to fall in the last feast of pneumatic drills. However, we still receive reminders of the world that we have paved over and littered with mushrooming forests of steel and plastic and cement.

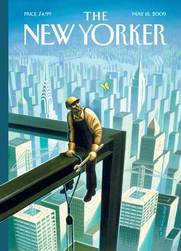

“Eric Drooker’s”:http://www.drooker.com cover for the May 18, 2009 issue of _The New Yorker_ gives us such a reminder.

A single yellow butterfly, a forgotten little animal, rises above the sterile city and shows itself to one of the city’s builders. We are not sure if the wrench-wielding construction worker looks upon the creature with disgust, apathy, hope, or anger -but at least he’s looking. Is it a life-changing moment? Perhaps not. But at least it’s stopped him, at least for a moment, from helping to elevate these peaks of cement still further.

Drooker’s cover is named “Coming Up For Air,” and it is not just the butterfly that is coming up for air, but the solitary construction worker as well, perched on a girder high above the vertical limbs of the city. Thousands of feet up in the air, life reasserts itself.

There are in fact three living beings on this cover: the butterfly, the worker, and the city. In Drooker’s work, New York City metamorphoses as much as the nymphs and gods of Greek mythology do.

“A slideshow of his work”:http://www.cartoonbank.com/product_details.asp?mscssid=N75BLQT1QCKS9NR183NUWJWU397MBJ28&sitetype=1&did=5&sid=123086&pid=&keyword=eric+drooker§ion=all&title=undefined&whichpage=1&sortBy=popular will show you multiple New York Cities: you’ll see the city from different angles, from various perspectives, from surreal and fantastical approaches.

Drooker’s bird’s-eye views, dog’s-eye views, and worm’s-eye views reveal a city that is different things to different people. All you have to do is look up, look down, or look differently. There are viewpoints from pigeons and dogs and men on stilts. A homeless’-eye view reveals a different city, in which a bonfire in a trashcan provides limited protection in a cold winter’s night near Brooklyn Bridge.

Drooker not only works with oblique angles and aerial viewpoints but also works at transplanting the city, either parts of it or as a whole, into different temporal or geographic zones. A businessman emerges from a New York subway station located in some sweltering jungle. There exists a subway station with cave paintings, and an arctic subway station at 125,000 Street bustling with harpoon-wielding commuters. In various dimensions, there exists a neo-Egyptian New York; the Big Apple as a city of books; a surreal city of smokestacks; as a transplanted single building on a desert island; as a geographically ambiguous city as seen from a jungle with toucans and monkeys; as an electric blue metropolis of romance where two lovers kiss.

Drooker’s latest cover depicts a scene that is evocative of the 1930s, and especially of the famous 1932 “photo”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunchtime_atop_a_Skyscraper, by “Charles C. Ebbets”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_C._Ebbets, of construction workers lunching on a cross-beam. Our point-of-view is that of a bird or cloud; we float above the gaunt-faced construction worker, as freely as the butterfly that distracts him temporarily from his work.

Drooker, a native of Manhattan, does not stand at a distance from the city he depicts so frequently. He has worked as a tenant organizer, struggled against police brutality aimed at unlicensed street artists and musicians, and contributed to leftist magazines such as _People’s Daily World_, _The Progressive_, and _World War 3 Illustrated_. His first graphic novel, “_FLOOD! A Novel in Pictures_”:http://www.drooker.com/sequences/flood.html, is a wordless series of scratchboard images that evoke Lorca’s “forgotten little animals.” There is enough rain pouring down in _FLOOD!_ to drown the city’s inhabitants; one gets the feeling the city will nonetheless live on, inhabited by empty humming streetcars and roving hungry thylacines.

Drooker’s delicate butterfly is not just any butterfly, but the butterfly that “so entranced the first Eustace Tilley”:http://archives.newyorker.com/?i=1925-02-21 and successive generations of Eustace Tilleys. I don’t think “Rea Irvin”:http://www.printmag.com/Article.aspx?ArticleSlug=Everybody_Loves_Rea_Irvin had a specific butterfly species in mind when he first drew the butterfly that so captivated his monocled mascot, but I would like to put forward a possible candidate: _Colias philodice_, or in the common tongue, a Clouded Sulphur.

The Clouded Sulphur’s range includes New York City and its coloring and markings match the New Yorker’s butterfly. “Take a look.”:http://www.mariposasmexicanas.com/colias_philodice_eriphyle.htm

The cover is subtle in its message, and not as subtle one would expect from someone who in past decades organized rent strikes and drawn politically-charged posters and lapels. “I’m still very concerned with trying to persuade people of certain ideas, educate them,” Drooker “has remarked.”:http://www.robwalker.net/html_docs/drooker.html “But I think I could be more effective if the propaganda doesn’t _look like_ propaganda.”

Like the Clouded Sulphur, the message in an artist’s work has to flutter near us. Perhaps we’ll notice it; perhaps not.

Emdashes

Modern times between the lines