Author Archives: Emdashes

Sempé Fi: Squared Away

_Pollux writes_:

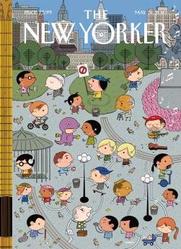

Double issue of _Sempé Fi_ today. Now we’re going to look at Ivan Brunetti’s cover for the May 31, 2010 issue of _The New Yorker_. It’s called “Union Square,” and depicts this New York landmark crowded with Brunetti’s typically diminutive, big-headed figures (Brunetti’s covers are easily recognizable). Even Henry Kirke Brown’s 1856 equestrian statue of George Washington is re-imagined in Brunettian form.

Union Square is usually the focal point for political protests. Brunetti’s Union Square has many people, but only of them can be described as a protestor: she wars a bandanna and holds a sign calling for the ban of something.

The point Brunetti is making is that the call for political action is drowned out by multiple iPods, Bluetooths, and headphones and the steady uproar of daily life. A man strums a guitar, a ponytailed yuppie whizzes by on a Segway, kids play, a man in a purple dinosaur suit hands out ads. As if emphasizing his point, Brunetti’s cover depicts the strings of a large guitar on its left margin. Brunetti’s lone protestor is engulfed by the park and by the skyline.

Who is listening to the protestor? No one. No one is up in arms because everyone’s arms are full with the needs and rhythms of daily life.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Certified Male

Sempé Fi: Boomerang

_Pollux writes_:

“Parents groan about the ‘boomerang’ generation,” Gerald Handel and Gail G. Whitchurch write in _The Psychosocial Interior of the Family_, “young adults who return to the nest and stay beyond the time when, in years past, they would have been expected to be independent. Parents send their kids out, but they keep coming back.”

And certainly the parents featured on Daniel Clowes’ cover for the May 24, 2010 issue of _The New Yorker_ look dismayed to see the return of their adult son. Clowes’ cover, called “Boomerang Generation,” refers to a social phenomenon of our time: grown children, often college graduates, who are retying the apron strings.

Clowes depicts an amusing but credible scene: a student, having recently earned his PhD, hanging his diploma alongside past triumphs from his elementary and high school days. The student has returned home; he is surrounded by luggage and boxes. Tim is once again occupying “Tim’s Room.” Parents, keep out (unless you’re there to collect laundry or trash).

His parents look on, saddened and disappointed. Perhaps they had hoped to turn “Tim’s Room” into a gym or a room they could rent out.

What now for Clowes’ newly minted graduate? Will he sit around, getting his laundry done by maternal hands and visiting his old haunts? Will he reflect on how small his bedroom feels compared to the campus dorm he shared with two roommates from Uruguay and Taiwan, respectively? What will he do with his dissertation on Livonian peasant culture?

The trend of a Boomerang Generation, which merits an entry in the _Encyclopedia of Social Problems_ (it comes after “Body Image”), is linked to multiple causes: young adults marrying later, fewer employment opportunities, the high cost of housing.

But for whom is this a problem? The parents or the children? For the children, becoming a boomerang seems less of a social problem and more of a solution. It makes economic sense. Whether the children become psychologically stunted or not, the thought of how much money is being saved cancels out any possible paraphilic infantilism or diaper fetishism.

For the parents, having their children return home may or may not be a cause for strife. As Vincent N. Parrillo writes in his _Encyclopedia of Social Problems_, “the unhappiest parents are those whose children have left and returned on several occasions, returning because of failure in the job market or in pursuit of education.”

We can lump the parents that Clowes depicts into that category of “unhappiest parents.” But they should not despair. Tim is finding his own way, and one day, while driving past his old high school (“Go Wildcats”), an idea or flash of inspiration will strike him, and he will embark on a new life’s journey.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Antiphallos the Abstinent Satyr

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: At the Genius Bar

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: With a Porpoise

Gary Coleman, 1968-2010

_Pollux writes_:

“Why should I be afraid of the camera?” Gary Coleman asked, in an April 1979 interview in _Ebony Jr._ magazine (Vol. 6, No. 10). “If it wore a black cape and had fangs, I’d be scared of it. But since it doesn’t, then why be afraid? There’s really nothing to this.” Coleman was eleven at the time. _Diff’rent Strokes_, of which Coleman was the life and soul, had already been on the air for four months.

By the time Coleman celebrated his 21st birthday, the actor had attempted to take control of his life, and his finances, by suing his parents and former manager for mismanaging his $3.8 million trust fund. His life had become a mixture of misfortune and success. Celebrities attended the actor’s 21st birthday. The mayor of Los Angeles, Tom Bradley, declared February 8 to be “Gary Coleman Day.” Coleman cut into an enormous birthday cake shaped like a train (the actor was a model train aficionado).

By 1999, Coleman had filed for bankruptcy and his life was a downward spiral of legal, domestic, and police troubles. Coleman’s calamities seemed to engender more derision and Schadenfreude than understanding.

He had become a punch-line and a pop culture trivia question: Did you know Coleman had worked as a security guard on a movie set? His misfortunes did not always bring out the best in people, or in the media.

Coleman’s life was a reverse image of the American dream. His riches-to-rags story became a subject for parody. There was a character named Gary Coleman in the musical _Avenue Q_. The song “It Sucks to Be Me” captured the tragedy of his life: “I’m Gary Coleman / From TV’s Diff’rent Strokes / I made a lotta money / That got stolen / By my folks! / Now I’m broke and / I’m the butt / Of everyone’s jokes.”

I stood next to Gary Coleman once while in line at a Pavilions supermarket in Culver City. Often, when an actor ages, he or she loses whatever spark that made the actor an object of affection or admiration.

But as Coleman chatted with the checkout girl, one could still see the same boy who, back in 1979, was completely unafraid of the camera. Despite his misfortunes, the bubbling confidence was still there, and to which we should pay tribute.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Accented

Will Gary Coleman’s Death Affect the Gary Coleman Role in “Avenue Q”?

Emily Gordon writes:

The blog Instant Tea, part of the Dallas Voice, asks the same question, as does the Washington Post, in this live chat exchange (the questioner is not, I assume, anyone from the actual show):

Avenue Q: Do the producers retire its “Gary Coleman”?

Hank Stuever: Hmmm. Good question. Get me rewrite. There are so many living, washed-up tv stars to sub in.

Maybe our friend Ben Bass can provide some insight, since he knows the folks behind the musical. Having reported a rejected Talk of the Town piece back when Obama was elected, about whether the line “George Bush is only for now!” would be replaced (they decided to keep it), I have a hunch they may hold on to the Gary Coleman character, too.

Besides, how many leading parts for black women (Coleman is played by a woman; in New York, currently by Danielle K. Thomas) are there in high-profile, touring shows? Not that many. I vote to preserve Coleman’s memory in this highly affectionate, vibrant portrayal of what his life might have been if he’d taken another path. Till our dreams come true, we live on Avenue Q.