Author Archives: Emdashes

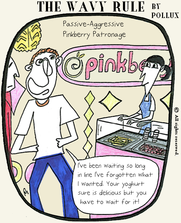

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Passive-Aggressive Pinkberry Patronage

Irreplaceable Magazines, Irreplaceable Editors

Martin Schneider writes:

Jason Kottke today linked to some scanned pages of Sassy from the early 1990s. Jason observes, “Sassy seems to be one of those rare magazines that is dearly missed but doesn’t really have a modern day analogue. (See also Might and Spy.)”

True enough. What occurred to me, however, was that those three magazines have something in common: a very strong editorial hand. In all three cases the editors are pretty well-known people: Jane Pratt in the case of Sassy, Dave Eggers for Might, and Kurt Andersen/E. Graydon Carter for Spy. So the reason they either don’t exist or have not been replaced is that those specific people have elected to do other things.

But it feels like the “rule” of a strong, irreplaceable editor needs more to it. There are other magazines run by strong editors where it’s easy to imagine the magazine continuing in that editor’s absence. Anna Wintour at Vogue, for instance. David Remnick at The New Yorker. Carter at Vanity Fair.

So we can add a corollary. The irreplaceability of an editor is inversely related to the size of the operation, expressed in terms of circulation, revenue, ad pages, whatever.

Let’s stick with circulation for a moment. One way that a magazine becomes “a big deal” is when it expresses the hopes, dreams, fears, etc. of an impassioned, interested sliver of the population. That was true for Sassy and Spy, certainly; not so sure about Might but let’s say it’s true there too. As a counter-example, you could imagine that being true of Wired, say, but Wired got too big and important—that is to say, its readership combined an impassioned sliver and a larger group that was only mildly interested in the content. In other words, its readership had “graduated” to a general readership, making it possible for Wired to have multiple editors over time.

So I’d ask two questions: Are there any other magazines in Jason’s group? Do 2600, Raygun, SPIN, The Comics Journal, Adbusters count as potential members of that group (potential, since some of them still exist) or not? Who are the editors of those magazines? I can name three of them off the top of my head, but I won’t say which ones.

The other question is, Are there magazines that break my rules? One magazine that I had in mind for this category was Interview, which was founded by Andy Warhol and decidedly represented a “sliver” of the reading public, but it’s been chugging along for quite a while now. Is it an exception, or did its revenue or something pass some benchmark way back when? I don’t know the answer.

Sempé Fi: The Thin Black Line

_Pollux writes_:

The May 17, 2010 issue of _The New Yorker_ was The Innovators Issue. The issue’s cover, called “Novel Approach,” by the Dutch artist “Joost Swarte”:http://www.joostswarte.com/, captures the process of invention and inspiration, and the insanity that drives them both.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, scientists and thinkers were obsessed with solving the problem of longitude. In our own day, we are concerned with solving the issue of global warming.

In “Novel Approach,” Swarte gives us a wordless comic in his trademark _ligne claire_ style. As Sean Rogers elegantly “put it”:http://www.walrusmagazine.com/blogs/2009/06/16/joost-swarte-further-summer-reading/, “Swarte’s drawings communicate so clearly because they’re executed in so concise and direct a fashion. Clarity of line engenders clarity of thought: each line set to paper acts as one element among equals, like a term in a balanced equation, or a word in a sentence that comes quickly but elegantly to the point.”

In “Novel Approach,” however, we are presented with a series of drawings that are open to various interpretations. Are we following a linear story, or, unguided by captions or balloons, can we start at any point in a series of panels that symbolize the fits and starts of innovation?

If we take a closer look at Swarte’s drawings, I believe there is a linear story here. It is the story of global warming and man’s tardy efforts to solve this problem.

Swarte’s hero, a bald, bespectacled man, is reading a newspaper -which perhaps is running stories on the issues of climate change. While he does so, numerous forms and shapes, all black in color, hover, enshroud, inspire, or approach Swarte’s hero.

Black smoke in various forms and increasing intensity emerges from the man’s pipe; from a passing car; from a large truck. In the second row of panels, black smoke belches forth from a factory.

In the next illustration, the man is alarmed by the levels of bovine flatulence. Do cow farts cause global warming? According to “The Straight Dope”:http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/832/do-cow-and-termite-flatulence-threaten-the-earths-atmosphere, “animal methane does present a definite threat to the biota. It’s believed 18 percent of the greenhouse effect is caused by methane, putting it second on the list of offending gases behind carbon dioxide.”

In the next drawing, a black sun angrily glares at the man, who is engrossed in his newspaper. The sun is warmer and more dangerous.

In the third row, we see the effects of global warming: emigrating penguins; a large, black tidal wave, symbolizing the increased threat of tsunamis; and flooding. Swarte’s hero wades through black waters. It doesn’t seem to disturb him; in fact, it is moving him closer to an idea.

In the last row, he gets a flash of inspiration while swimming underwater. The world is perhaps covered by a Panthalassic Ocean.

His idea? A propeller beanie (also colored black) that will allow him to read his newspaper in peace amongst the clouds. Will it come to that? Swarte’s hero does not solve the issue of global warming at all; his novel approach, which is also the surreal approach of a mad fool, is simply to sit atop the clouds while our world turns into a water planet.

Swarte’s clean lines provide us with a future that is all too frightening in its clarity. Will we take action before it’s too late or will we all drown in an angry sea cluttered with empty cans and dead fish?

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: H-E-Double hockey sticks

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Urning Power

Lessons of the Great “Social Security Reform” Fracas of 2005

Martin Schneider writes:

In 2005 I attended a debate on the then-hot topic of “Social Security Reform,” featuring Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo, Paul Krugman of The New York Times, and Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute. I was reading a transcript of the debate earlier this evening, and I was struck by an odd parallel or perhaps mirror relationship between that political fight, which the Democrats won, and the fight to pass the Affordable Care Act in 2009-10, which the Democrats won.

The parallel I’m interested in is not that the Democrats won both fights. Rather, the resemblance has to do with what a ruling party does when it pushes an ambitious reform that is not very popular.

A little bit of context. The debate took place on March 15, 2005. After his reelection in 2004, George W. Bush chose to move forward on a favored policy idea of his, Social Security Reform. The Republicans had initially called the project “Social Security Privatization,” but after noticing how poorly that term polled, they switched up their terminology and began accusing Democrats of having attempted to demonize them with this term, “privatization.” (Something very similar happened later the same year with the term “nuclear option.”) The “private accounts” morphed into “personal accounts”—Republicans generally began running away from their own terms.

That spring, Marshall had a huge amount of fun trying to make Republican congresspersons squirm by asking them whether they supported Bush’s plan on Social Security (whatever name you gave it). Over those weeks, it became harder and harder to get any Republican congressperson to state on the record that they supported privatizing Social Security. The plan fizzled out, in the face of Democratic unity in favor of preserving the current system for the time being.

(I mentioned that Marshall got some enjoyment by embarrassing and neutralizing these Republicans. That is a massive understatement; I think when Marshall looks back on his illustrious career of Internet muckraking, this episode, in which he tarred this or that Republican a “bamboozler,” will be on the short list of the most satisfying moments of all.)

In the debate, Marshall was asked to describe the political aspect of the battle over Social Security reform (as opposed to the substantive side). In his opening remarks, Marshall said this:

The second thing is, and Democrats did this very quickly, is their party unity took away all the political cover. It was really going to be up to Republicans to make privatization an entirely Republican enterprise, and they were too afraid to do it because a lot of those representatives could see how their constituents were going to react and so forth.

Re-reading the transcript tonight, it was this passage that reminded me so much of the fight to pass the ACA (what used to be known as “the health reform bill”). That phrase, “an entirely Republican enterprise”…. that’s the position the Democrats were in all of last year, wasn’t it? You bet it was.

A person might conclude from this that Democrats and Republicans both obstruct, but that the Democrats happened to be better at it (aided by a larger minority than the Republicans now have). But I think there’s something more fundamental going on that tells you a great deal about the two parties and what they stand for.

Consider these two statements:

In 2005 the Republicans, in control of the White House and Congress, proposed a bold new reform that would affect a key area of American life, and it didn’t poll very well, and as soon as the unpopularity of the proposal was made apparent, the Republicans dropped the policy when they realized that it would be associated solely with Republicans.

In 2009-10 the Democrats, in control of the White House and Congress, proposed a bold new reform that would affect a key area of American life, and it didn’t poll very well, and as soon as the unpopularity of the proposal was made apparent, the Democrats, with a great deal of difficulty, passed the policy even though they realized that it would be associated solely with Democrats.

To put it more simply, both parties were given an opportunity to foist their favored policies on the nation in a unilateral way. The Republicans did not want to be associated with their own stated policies, but the Democrats were willing to be associated with their own stated policies.

I have a few conclusions about this, which may reflect my political bias.

Conclusion 1: By and large, Republican positions are minority positions, and Democratic positions are majority positions. Or to put it another way, the Bush administration and the Republican Congress of 2002-2007 found it difficult to implement their ideas because they were favored by such a small portion of the electorate. The Democrats of 2010 do not have this problem; their ideas held by a great many people, broadly speaking.

Conclusion 2: Democrats are sincere about their policy ideas; Republicans are not. I don’t want to overstate this too much, but there is more than a kernel of truth to it. Republican ideas ideas sound appealing and have some populist appeal but would have pernicious effects. Republicans express generalized distaste for the government services, but a lot of that is just rhetoric, and when push comes to shove, they are not very interested in decreasing those services. Contrariwise, the Democrats are more willing to argue for the benefits of social services and intelligent deployment of government generally, and when the going gets tough, it turns out that they actually do believe that.

And lastly,

Conclusion 3: Democratic ideas are good ideas; Republican ideas are bad ideas. Again, don’t want to take this too far. But the fight in 2005 was between a group that wanted to kill or at least diminish Social Security in favor of retirement accounts tied to the stock market in some broad way. Surely, the stock market crash of 2008 reveals this to have been a terrible idea.

Similarly, the fight of 2009-10 was between a group that wanted to provide uninsured people with health care and a group that was quite happy to keep them uninsured. Democratic ideas are easier to defend not only because they are popular but also because they are genuinely good ideas.

Thus endeth the sermon.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Famous Archers

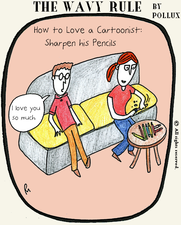

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: How to Love a Cartoonist

Sempé Fi: Winds of Change

_Pollux writes_:

Some _New Yorker_ covers require some explanation, and this is certainly the case with the cover for the May 10, 2010 issue of _The New Yorker_. _Sempé Fi_ is here to help.

Bob Staake’s “Tilt” features a Pilgrim riding a whale tilting a lance at a wind farm in the middle of the ocean. The imagery, and title, refer to Don Quixote. The focus of the cover, however, is on the waters off Massachusetts (hence the Pilgrim) rather than the sun-drenched fields of La Mancha. Specifically, the covers refers to the controversial Cape Wind project, the United States’ first offshore wind farm.

Composed of 130 wind turbines, Cape Wind is to be built on Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket Sound. Public opinion survey results reveal that most Bay Staters support the project and its goal of providing clean, renewable energy, but opponents include the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, which cites economic, environmental, and aesthetic concerns.

Greenpeace, however, supports Cape Wind, and has its own concerns about the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, “accusing”:http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/campaigns/global-warming-and-energy/copy-of-wind-power/in-support-of-cape-wind/greenpeace-support-s-cape-wind the organization of disseminating false and misleading information about the Cape Wind project. Greenpeace alleges, for example, that the Alliance of falsely tripled the size of Cape Wind in the Alliance’s description of the controversial project, as well as depicting Cape Wind to be much closer to shore than it would be.

Interestingly, the wording that the _Boston Globe_ used for its coverage on this distortion evokes Staake’s imagery: “Foes tilt at larger-than-life Cape Windmills – Error in flier inflates the size of proposed turbine farm in Nantucket Sound.”

And so the battle rages. Staake’s round little Pilgrim tilts a lance at a towering wind turbine, but it is an ineffective lance.

Both the Pilgrim and the whale are dwarfed by the powerful-looking and triumphant towers of Aeolus. The Pilgrim’s old fashioned weapon and clothing evokes the futile and somewhat backward-looking opposition to the Cape Wind project. “It is easy to see,” Don Quixote says to Sancho just before battling the windmills, “that you are not used to this business of adventures. Those are giants, and if you are afraid, away with you out of here and betake yourself to prayer, while I engage them in fierce and unequal combat.”

_Cape Cod Today_ “interviewed”:http://www.capecodtoday.com/blogs/index.php/2010/05/03/cape-wind-makes-new-yorker-cover?blog=53 Staake regarding this cover. “Like most of us here on the Cape,” Staake remarked, “I have mixed feelings about the project and I think the cover reflects that, though I have to say I think it’s pretty cool that in a few years my Chatham studio will be powered by wind.”

Would any future disaster involving Cape Wind reach the magnitude and create the damaged wreaked by the Deepwater Horizon disaster? Are wind farms beautiful to look at? Would sea life be adversely affected by the presence of a wind turbine?

In any case, the debate may be moot: Ken Salazar, the Secretary of the Interior, gave the project the green light in late April. Staake’s whale-riding, lance-wielding Pilgrim cuts a silly figure against a backdrop of turbines slicing the sky.

As with any major development project, there are pros and cons, mixed feelings, rational opposition, irrational opposition, strong support, and fierce and sometimes unequal combat. Bob Staake’s “Tilt” captures the spirit of this combat and debate.