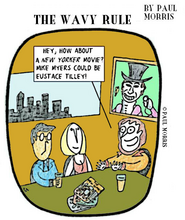

This week, we published the first and second of Paul Morris’s new daily comic for Emdashes, “The Wavy Rule.” Today’s edition is below–click to enlarge.

This week, we published the first and second of Paul Morris’s new daily comic for Emdashes, “The Wavy Rule.” Today’s edition is below–click to enlarge.

Last night, I kissed Restaurant Florent goodbye–really kissed it, with my mouth, and salted my veggie burger and champagne with a Liechtenstein-sized tear. It’s inconceivable that the restaurant, which houses many memories for those who spent time in the West Village before All This, won’t exist after this Sunday, but it’s so. Get there while you can; the atmosphere, as well as the legendary menu board, is festive-tragic. Go. Didn’t Malcolm Gladwell say that when something you’d come to count on in New York suddenly disappears, whether you’ve been here a month or a year, you become a true New Yorker? That happened a long time ago for many, but maybe this weekend will produce many a mussel-colored hash mark for loyal service rendered, especially, of course, by Florent Morellet himself.

Who will report Florent’s last day for The New Yorker, I wonder? I’d be glad to read a Talk of the Town by Ben McGrath, Lauren Collins, Rebecca Mead, or Michael Schulman on the ultimate order, but if there’s a longtime contributor who loves the place (say, Lillian Ross, although I can’t quite picture it), or a chronicler of New York who wants to make a special visit (Pete Hamill comes to mind), I would love to read his or her account. Gladwell is a neighbor of the place, and Leo Carey could also do a lyrical restaurant-review-final-day mashup.

I asked Martin to see if there were any references to Florent in the Complete New Yorker, and here’s what he found. From a January 19, 2004 Talk by Lauren MacIntyre, about housing in the West Village:

One person’s avant-garde, though, is another’s antique. One of the meatpacking district’s better-known businessmen, Florent Morellet, the owner of Florent, the sleek Gansevoort Street diner that is popular with both cross-dressers and corporate financiers, began to speak out in support of the house. Alarmed by the brushfire development around the Gansevoort Market, Morellet helped push to have the area designated a historic district (a proposal that just passed), yet he also praised the plans for 829 Greenwich Street, calling the use of steel building materials “authentic” to the history of the neighborhood. Last spring, when Baird and his team presented their design to the Landmarks Commission, the board voted unanimously in favor of it, and last February the old place was finally demolished.

To celebrate the groundbreaking, Baird threw a party at Florent just before the new year. Baird and the woman who owns the house (her husband was out of town) strolled amiably among the guests. Hanging in the restaurant’s entryway was a large computerized rendering of the house. People commented on the huge steel façade, which, if it is trucked into the city, will necessitate a temporary shutdown of the George Washington Bridge.

“It weighs seventeen tons,” a man said.

And from a Tables for Two restaurant review of “Pre:Post” in the July 3, 2006 issue, by Nick Paumgarten:

“Even before the meatpacking district became hell, there was a respite from it, at Florent, the regenerative twenty-four-hour bistro. Not so in West Chelsea, the night-club vortex up the avenue, where the right kind of late-night chow has long been scarce as silence. Such, anyway, is the theory, or one of the theories, behind Pre:Post, a new dusk-to-dawn restaurant where the slick kids are encouraged to gather and dine before and after their submersion into the clubs down the block.”

Finally, something I happened on recently, also in the Complete New Yorker jewel box, brought Florent to mind. It’s a Talk from June 6, 1925, and as with a number of those early number, the author is unknown:

Note on a Passing

Joel’s has closed; perhaps the last of the older order of restaurants, whose hosts were individuals, not corporations. It was never a gaudy, nor a gilt-edged establishment; that one on Forty-first street, with its green-tinted door; and its heydays were ten, or even fifteen years behind when it surrendered to the inevitable.

But it did know heydays, such as would lead a profitable procession of American tourists to visit it still if Joel’s were in Paris, or London, instead of a few doors west of the second-hand clothing marts of Seventh avenue; and how picturesque, by the way, these would be in, for instance, Vienna.

There was in Joel’s on the night it clossed, the table at which Sidney Porter used to sit, back to the window, looking on life. And another that knew the young Booth Tarkington many a long night years ago. The older Mark Twain looked in occasionally. Alfred Vanderbilt was a patron in those times when it was the thing to stay up all night on the eve of a Vanderbilt Cup race and drive through the greying dawn to the Jericho turnpike to look on the daring of Barney Oldfield and the like.

George Luks was seen there often, and Alan Dale when his caustic comments were feared far more than the ponderous pronouncements of the venerable William Winter, another patron of Joel’s. It was, too, a favorite resort for earnest Mexican revolutionists before that nation substituted the ballot for the bullet in presidential elections. This last, probably, because Joel Rinaldo served admirable chili con carne when that dish was almost unknown elsewhere in New York.

Fare thee well, all things Florent.

This week, we introduced Paul Morris’s new daily comic for Emdashes, “The Wavy Rule.” Today’s installment is below–click to enlarge.

Back in April, I posted about The New Yorker’s (TNY) recent propensity for publishing British fiction that (sometimes) requires translation, at least for those of us who grew up talking ’merican instead of the Queen’s English.

Little did I know at the time that the pleasure of doping out the lingo of our cousins across the pond had been systematically stolen from oodles of American readers of Harry Potter. That’s right: the U.S. editions of the Potter books (pre-2000, anyhow) were, um, bowdlerized (albeit unevenly) with the cooperation of the author, as Daniel Radosh reported in the September 20, 1999 issue of TNY.

Unfortunately, the complete version of Radosh’s “Talk of the Town” piece isn’t available online, so I urge those of you with the Complete New Yorker to check it out in its entirety. For the rest of you, here’s a taste:

In the American edition, “wonky” becomes “crooked”; “bobbles” turn into “puff balls”; and “barking mad” translates to “complete lunatic.” “Git,” “ickle,” and “nutters,” however, are left as they are. Why does Father Christmas become Santa Claus, and “bogey” become “booger,” but “budge up” not become “move over”?

Ah, well. Hard enough on the editors as it was, making sure they switched all the single quotation marks for double quotation marks, and vice versa.

In the latest New Yorker Out Loud podcast, Matt Dellinger talks to Atul Gawande about “The Itch,” an investigation into (eek) uncontrollable itching:

Dellinger: Did you itch a lot while writing the piece?

Gawande: Constantly. At various points I would imagine there was a bug on my flank or in my hair, and I’d just have to get up and walk away. At one point I literally did ask my wife to just look and make sure that I didn’t have a bug in my hair!

We’re delighted to announce that Emdashes will be publishing a daily comic by friend and fellow New Yorker admirer Paul Morris, on themes typographical, historical, and technological, on personalities of all kinds, and, of course, on the magazine past and present. It’s called “The Wavy Rule” in honor of Rea Irvin‘s signature squiggly line.

Born in Beverley, England, Paul has a B.A. in History from UCLA and a Master’s in History from Brown University. Since 2006, he’s written and drawn a webcomic called “Arnjuice.” You can see more of his work on his Flickr page, and he has collections for sale at Lulu. He’s currently studying graphic design at the Art Institute of California, Los Angeles.

We’re so pleased to have him drawing for us–we think he’s a perfect addition to the crew. If there’s a New Yorker-related or other idea you’d like see Paul draw, please email us and we’ll pass it along for his consideration. After the jump, the first installment of “The Wavy Rule,” inspired by Paul Goldberger’s recent story “The Forbidden City,” about the makeover of Beijing.

From today’s Manhattan User’s Guide (links are mine):

One of the most memorable books we’ve ever read is Philip Gourevitch’s We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda, a heartbreaking account of the unspeakable genocide there. In Mr. Gourevitch’s new book, Standard Operating Procedure, written with documentary filmmaker Errol Morris, we get the full horrors of Abu Ghraib. The authors will be at Barnes & Noble on W. 82nd this Monday night, 7pm.

At City Room, Jennifer 8. Lee has a thoughtful riff on E. B. White’s searing, searching essay “This Is New York”—an excerpt from which is running on the subway as part of the “Train of Thought” series—and White’s description of the “roughly three New Yorks”:

There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born there, who takes the city for granted and accepts its size, its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter–the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night.

Third, there is New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something. Of these trembling cities the greatest is the last–the city of final destination, the city that is a goal. It is this third city that accounts for New York’s high strung disposition, its poetical deportment, its dedication to the arts, and its incomparable achievements.

As Lee writes, “The selection, which is supposed to represent a slice of history, seems particularly meaningful on the subway.”

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Bet you’ve always wanted to see a snapshot of the (James) Thurber family Airedale. Or cartoonist Charles Addams’ dog. Now you can, thanks to aterrier, a delightfully obsessive blog that tracks famous terriers. Don’t miss the entries on Tintin’s dog, Snowy, or news of a diary by Dorothy’s own Toto.

on Slashdot—a lively discussion of Elizabeth Kolbert’s recent piece.